Oliver plucks up a spirit — the third steel engraving and later watercolour for Charles Dickens's The Adventures of Oliver Twist; or, The Parish Boy's Progress, first published in volume by Richard Bentley after its April 1837 appearance in Bentley's Miscellany, Chapter VI. 4 ½ by 3 ¾ inches (11.3 cm by 9.5 cm), vignetted, facing page 31 (originally leading off the monthly instalment). Cruikshank's own 1866 watercolour, commissioned by F. W. Cosens, is the basis for the 1903 chromolithograph. [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Passage Illustrated: Hectoring Noah's Comeuppance

"Work'us," said Noah, "how's your mother?"

"She's dead," replied Oliver; "don't you say anything about her to me!"

Oliver's colour rose as he said this; he breathed quickly; and there was a curious working of the mouth and nostrils, which Mr. Claypole thought must be the immediate precursor of a violent fit of crying. Under this impression he returned to the charge.

"What did she die of, Work'us?" said Noah.

"Of a broken heart, some of our old nurses told me," replied Oliver: more as if he were talking to himself, than answering Noah. "I think I know what it must be to die of that!"

"Tol de rol lol lol, right fol lairy, Work'us," said Noah, as a tear rolled down Oliver's cheek. "What's set you a snivelling now?"

"Not YOU," replied Oliver, sharply. "There; that's enough. Don't say anything more to me about her; you'd better not!"

"Better not!" exclaimed Noah. "Well! Better not! Work'us, don't be impudent. your mother, too! She was a nice 'un she was. Oh, Lor!" And here, Noah nodded his head expressively; and curled up as much of his small red nose as muscular action could collect together, for the occasion.

"Yer know, Work'us," continued Noah, emboldened by Oliver's silence, and speaking in a jeering tone of affected pity: of all tones the most annoying: "Yer know, W ork'us, it can't be helped now; and of course yer couldn't help it then; and I am very sorry for it; and I'm sure we all are, and pity yer very much. But yer must know, Work'us, yer mother was a regular right-down bad 'un."

"What did you say?" inquired Oliver, looking up very quickly.

"A regular right-down bad 'un, Work'us," replied Noah, coolly. "And it's a great deal better, Work'us, that she died when she did, or else she'd have been hard labouring in Bridewell, or transported, or hung; which is more likely than either, isn't it?"

Crimson with fury, Oliver started up; overthrew the chair and table; seized Noah by the throat; shook him, in the violence of his rage, till his teeth chattered in his head; and collecting his whole force into one heavy blow, felled him to the ground.

A minute ago, the boy had looked the quiet child, mild, dejected creature that harsh treatment had made him. But his spirit was roused at last; the cruel insult to his dead mother had set his blood on fire. His breast heaved; his attitude was erect; his eye bright and vivid; his whole person changed, as he stood glaring over the cowardly tormentor who now lay crouching at his feet; and defied him with an energy he had never known before.

"He'll murder me!" blubbered Noah. "Charlotte! missis! Here's the new boy a murdering of me! Help! help! Oliver's gone mad! Char—lotte!" [Chapter VI, "Oliver, Being Goaded by the Taunts of Noah, Rouses into Action, and Rather Astonishes Him," p. 31 in the 1846 edition]

Commentary: Oliver Rebels against Bullying

Again, slight but plucky Oliver asserts himself, here acting as the nemesis of the arrogant bully Noah Claypole at the undertaker's. Noah's hectoring about the immorality of Oliver's mother rightly incenses the boy, promoting him to assault an older and more physically powerful boy. Needless to say, the reader's sympathy, reinforced by the illustration, is with the indignant Oliver.

in these early illustrations for the novel, what we see is the result of a relatively harmonious collaboration between the veteran illustrator George Cruikshank, recognized at the time as the worthy successor to artists such as Hogarth, Rowlandson, and Gillray as a visual satirist, and the rising twenty-five-year-old writer, cited by one reviewer in the Spectator on 26 December 1836 as the Cruikshank of contemporary writers. This subject, like Oliver's asking for more and Oliver 's narrowly escaping being apprenticed to a chimney-sweep, was one which Dickens directly proposed to his illustrator for Bentley's Miscellany. Shortly, as Dickens and Cruikshank quarrelled over who should be the lead artist, the collaboration ceased to be so effective. The rocky relationship endured, however, from 1835 to 1841, from Sketches by Boz to the Pic Nic Papers, and Dickens generously (and wisely) approached the illustrator on behalf of Bradbury and Evans in 1845 to design the serial wrapper for the monthly parts.

Cruikshank followed Dickens's lead as he deployed more and more Hogarthian emblems in Oliver to reinforce aspects of character, plot, and theme. Cruikshank's use, for example, of objects of art is effective, though not as profound as it was in the Sketches by Boz or as the use made of them by Phiz in subsequent novels. [Cohen 24]

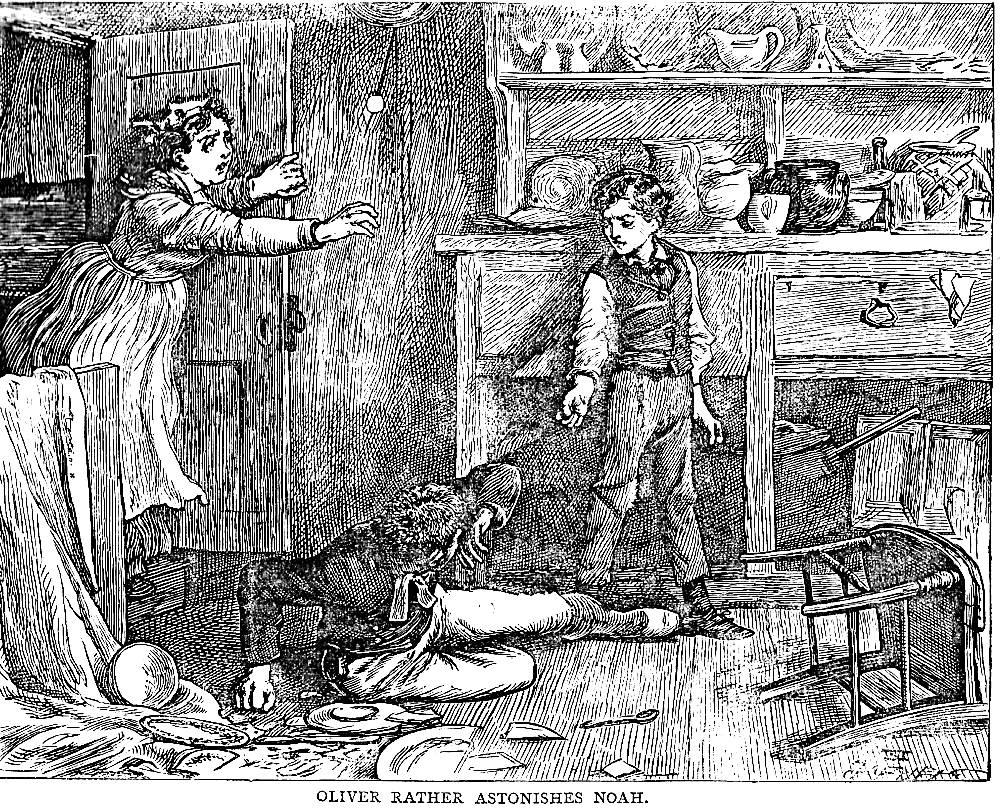

As the present illustration suggests, Cruikshank excels at depicting violence and repressed emotion with explosive force, and grotesquerie such as Noah Claypole's grimacing. The highly detailed depiction if the Sowerberry parlour in Cruikshank's illustration for the sixth chapter anticipates the interiors of Phiz in later novels, with elements of the composition that comment obliquely on the nature of the relationship between the recently arrived Oliver in clothing too small for him, the fashionably dressed undertaker's wife, and Noah, the egocentric charity boy whom Sowerberry has taken on as his assistant and who delights in tormenting Oliver. Cruikshank's organization of the dramatic scene is masterful, with each character in an appropriate pose, the juxtapositions of the four revealing their attitudes to one another, and the whole shaped into a pyramid with the wide-mouthed Mrs. Sowerberry (centre, rear) at the peak, the cowering, gangly-legged Noah at the base, right, and the overturned table drawing the eye to the left-hand corner. As in the accompanying narrative, Oliver in combative stance is centre, and the muscular Charlotte, trying to restrain him, left of centre. The women's fashions, as well as Noah's breeches and stockings, are consistent with the period of the early 1830s — we note as our eyes pass over the background details that another pair of Noah's stockings are drying on the clothesline, implying how well established he is in this kitchen and underscoring Oliver's being the outsider.

Complementing the pyramidal and rectangular forms underlying the scene are the emotional postures. Charlotte's raised fist draws the eye upwards, to the clothing on the line, but also connects Oliver's face, filled with indignation, and diagonally downward and right, to Noah's ineffectually raised elbow and terrified expression. The lighting and the expressions of the women and Noah all direct the reader's attention to Oliver, who himself is two pyramids: his arms, shoulders, and head form the upper pyramid, his legs, spread wide apart, forming the lower pyramid. He is doubly grounded, then, contrasting the rectangular blocks of chair, archway, door, and sideboard, all crowded into a tight space — incidentally, when Dickens was writing and Cruikshank at his instigation illustrating this scene, the author was anticipating his move from his relatively cramped bachelor's suite at Furnival's Inn to the more spacious accommodations of the townhouse at Doughty Street.

But what impresses the reader most about the composition is its wonderful communication of kinetic energy, for Oliver at the centre (in profile, with yet more to be revealed about his character and fortunes) is the driving force of the action here, even as he is the catalyst for the action of the entire story. This dynamic quality of the figures realizes visually the verbs and verbal forms, gerunds and gerundives, and numerous present and past particles (nodded, curled, continued, emboldened, speaking, jeering, affected, annoying, helped, looking, labouring, transported, started, chattered, dejected, roused, heaved, blubbered, etc.). The picture effectively captures the supporting attitudes of the other characters and the motivation of the protagonist; "the cruel insult to his dead mother had set his blood on fire" (31). The broken plates (far left), balancing the cowering apprentice (far right), imply that he, too, is about to be broken or shattered by the force of Oliver's temper. As Cohen notes of the animated quality of Cruikshank's figures,

If the characters in Cruikshank's cramped centripetal etchings for the Sketches by Boz seem possessed by "la violence extravagante du geste et du mouvement," said the French poet [Baudelaire, comparing Cruikshank's works to those of Breughel and Francisco Goya], those in Oliver Twist manifest "l'explosion dans l'expression," especially in the many scenes involving strong but repressed emotions. . . . [24]

Illustrations from the Household (1871) and the Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910)

Left: Harry Furniss's Charles Dickens Library Edition illustration of the same scene emphasizes the tremendous energy released in the figures of the three principles: Oliver aroused (1910). Right: James Mahoney's Household Edition realizes the aftermath, with Oliver triumphant as Charlotte rushes in: Oliver rather astonishes Noah (1871).

Left: Sol Eytinge, Junior's Diamond Edition wood-engraving of Charlotte and Noah absconding with the contents of Sowerberry's till, Noah and Charlotte (1867). Centre: Clayton J. Clarke's watercolour version of Noah Claypole (c. 1900). Right: F. W. Pailthorpe complements the beating with Oliver's first meeting the surly Noah: "Did you want a coffin, Sir?" (1886). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Related Material

- Oliver Twist as a Triple-Decker

- Oliver untainted by evil

- Like Martin Chuzzlewit, it agitates for social reform

- Oliver Twist Illustrated, 1837-1910

Scanned images and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. "George Cruikshank." Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio State U. P., 1980. Pp. 15-38.

Darley, Felix Octavius Carr. Character Sketches from Dickens. Philadelphia: Porter and Coates, 1888.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. Oliver Twist. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Bradbury and Evans; Chapman and Hall, 1846.

_______. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. 55 vols. Illustrated by F. O. C. Darley and John Gilbert. New York: Sheldon and Co., 1865.

_______. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Diamond Edition. 18 vols. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867. Vol. II.

_______. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. 22 vols. Illustrated by James Mahoney. London: Chapman and Hall, 1871. Vol. II.

_______. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. Vol. III.

Forster, John. "Oliver Twist 1838." The Life of Charles Dickens. Ed. B. W. Matz. The Memorial Edition. 2 vols. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott, 1911. Vol. 1, book 2, chapter 3. Pp. 91-99.

Grego, Joseph (intro)and George Cruikshank. "Oliver plucks up a spirit." Cruikshank's Water Colours. [27 Oliver Twist illustrations, including the wrapper and the 13-vignette title-page produced for F. W. Cosens; 20 plates for William Harrison Ainsworth's The Miser's Daughter: A Tale of the Year 1774; 20 plates plus the proofcover the work for W. H. Maxwell's History of the Irish Rebellion in 1798 and Emmetts Insurrection in 1803]. London: A. & C. Black, 1903. OT = pp. 1-106]. Page 12.

Kitton, Frederic G. "George Cruikshank." Dickens and His Illustrators: Cruikshank, Seymour, Buss, "Phiz," Cattermole, Leech, Doyle, Stanfield, Maclise, Tenniel, Frank Stone, Topham, Marcus Stone, and Luke Fildes. 1899. Rpt. Honolulu: U. Press of the Pacific, 2004. Pp. 1-28.

Created 17 August 2014 Last updated 10 January 2022