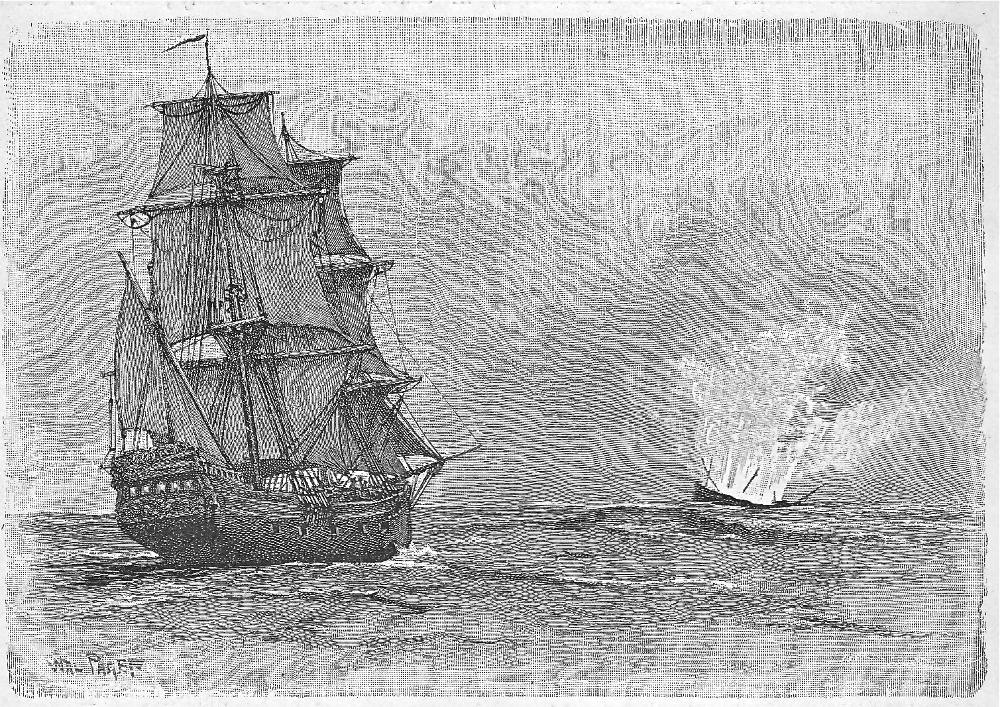

The French Ship on Fire (page 213) — the volume's fifty-sixth composite wood-block engraving for Defoe's The Life and Strange Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe of York, Mariner. Related by himself (London: Cassell, Petter, and Galpin, 1863-64). Part II, The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, Chapter I, "Revisits Island." Full-page, framed: 14 cm high x 22.3 cm wide.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

The Passage Illustrated: Another Disaster at Sea

We set out on the 5th of February from Ireland, and had a very fair gale of wind for some days. As I remember, it might be about the 20th of February in the evening late, when the mate, having the watch, came into the round-house and told us he saw a flash of fire, and heard a gun fired; and while he was telling us of it, a boy came in and told us the boatswain heard another. This made us all run out upon the quarter-deck, where for a while we heard nothing; but in a few minutes we saw a very great light, and found that there was some very terrible fire at a distance; immediately we had recourse to our reckonings, in which we all agreed that there could be no land that way in which the fire showed itself, no, not for five hundred leagues, for it appeared at WNW. Upon this, we concluded it must be some ship on fire at sea; and as, by our hearing the noise of guns just before, we concluded that it could not be far off, we stood directly towards it, and were presently satisfied we should discover it, because the further we sailed, the greater the light appeared; though, the weather being hazy, we could not perceive anything but the light for a while. In about half-an-hour's sailing, the wind being fair for us, though not much of it, and the weather clearing up a little, we could plainly discern that it was a great ship on fire in the middle of the sea.

I was most sensibly touched with this disaster, though not at all acquainted with the persons engaged in it; I presently recollected my former circumstances, and what condition I was in when taken up by the Portuguese captain; and how much more deplorable the circumstances of the poor creatures belonging to that ship must be, if they had no other ship in company with them. Upon this I immediately ordered that five guns should be fired, one soon after another, that, if possible, we might give notice to them that there was help for them at hand and that they might endeavour to save themselves in their boat; for though we could see the flames of the ship, yet they, it being night, could see nothing of us.

We lay by some time upon this, only driving as the burning ship drove, waiting for daylight; when, on a sudden, to our great terror, though we had reason to expect it, the ship blew up in the air; and in a few minutes all the fire was out, that is to say, the rest of the ship sunk. This was a terrible, and indeed an afflicting sight, for the sake of the poor men, who, I concluded, must be either all destroyed in the ship, or be in the utmost distress in their boat, in the middle of the ocean; which, at present, as it was dark, I could not see. However, to direct them as well as I could, I caused lights to be hung out in all parts of the ship where we could, and which we had lanterns for, and kept firing guns all the night long, letting them know by this that there was a ship not far off. [Chapter I, "Revisits the Island," pp. 212-14]

Commentary

The present illustration sets the keynote for the constant danger to which he exposes himself in his overseas experiences in the sequel, as the adventurer in his sixties encounters natural disasters and endures attacks by hostile peoples such as Tartars and the Indo-Chinese.

Thus far in the narrative-pictorial sequence, the house artists have provided four large-scale illustrations of shipwrecks and shipping disasters:

Indeed, if one regards shipping, shipwrecks, the sea, and sailors as a construct behind the illustrations, about thirty per cent of the Cassell's illustrations are associated with such a motif. A further twenty percent of the narrative-pictorial series involves foreigners and foreign locales. These melancholy events do not merely represent threats of the colonial and imperial enterprise and its inherent perils; they underscore the power of nature to frustrate human designs. Lest 21st century readers regard this repetition of maritime catastrophes with some skepticism, such periodicals as The Illustrated London News during the mid-Victorian period attest to the frequency of such wrecks, often as a result of storms. The year 1859 had proven especially perilous for British shipping.

Although shipwrecks in the age of Daniel Defoe, prior to the accurate mapping of shoals and the widespread construction of lighthouses, were all too common, as the British in the nineteenth century engaged in such preventitive measures, the number of catastrophic incidents declined. However, as The Illustrated London News for the 1850s and 1860s shows, hurricane force winds could still force even fairly large merchant vessels on the rocks, as in The Wreck of the "Royal Charter" on the Coast of Anglesea, near Moelfre Five Miles from Point Lynas Lighthouse (5 November 1859). The Cassell's house-artists appear to have based both shipwreck compositions on actual shipwrecks depicted in the pages of The Illustrated London News, such as Wreck of an Indiaman." — From a Picture by Mr. Daniell (16 February 1859).

What distinguishes this particular wreck from the others in the book is that it occurs far from land, and is not the consequence of a storm. The sea and sky reflect the suffering of those on board in what J. M. W. Turner would have termed "A Sky of Discord," although no storm rages, no waves engulf the vessel, and drowning sailors do not cling to the spars floating in the foreground. This is a man-made destruction, possibly the result of carelessness. The text reminds post-eighteeth-century readers that the North Atlantic served as the waterway between France and her North American colonies, particularly Quebec, which was not absorbed into the British Empire until 1759. As Crusoe had come to the rescue of Friday, the Spaniard, and the victims of the mutiny in Part One, he extends his sympathy to the oppressed and suffering, even if they are not English Protestants, in this instance coming to the assistance of French Catholics.

Related Material

- The Reality of Shipwreck

- Daniel Defoe

- Illustrations of Robinson Crusoe by various artists

- Illustrations of children’s editions

- The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe il. H. M. Brock at Project Gutenberg

- The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe at Project Gutenberg

Relevant illustrations from the other 19th c. editions, 1831 and 1891

Above: George Cruikshank's small-scale realisation of the disaster aboard the Quebec vessel, Crusoe sees a ship on fire at sea (1831). [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Above: Wal Paget's effective lithographic rendering of the calamity at sea, "The ship blew up." [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Above: Cruikshank's small-scale realisation of the suffering of the French passengers and crew, The French survivors of the fire aboard the Quebec Merchantman (1831). [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Bibliography

Defoe, Daniel. The Life and Strange Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe of York, Mariner. Related by himself. With upwards of One Hundred Illustrations. London: Cassell, Petter, and Galpin, 1863-64.

Defoe, Daniel. The Life and Strange Exciting Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, of York, Mariner, as Related by Himself. With 120 original illustrations by Walter Paget. London, Paris,and Melbourne: Cassell, 1891.

Last modified 25 March 2018