Thanks to the author and to Amanda J. Brettargh of JJ Books (London) for sharing the following discussion with the Victorian Web. Readers may wish to take a look at the JJ Books site, which includes a section in which “ well known writers to recall images that have inspired their work, from Brahma to Beardsley and beyond.” — George P. Landow.]

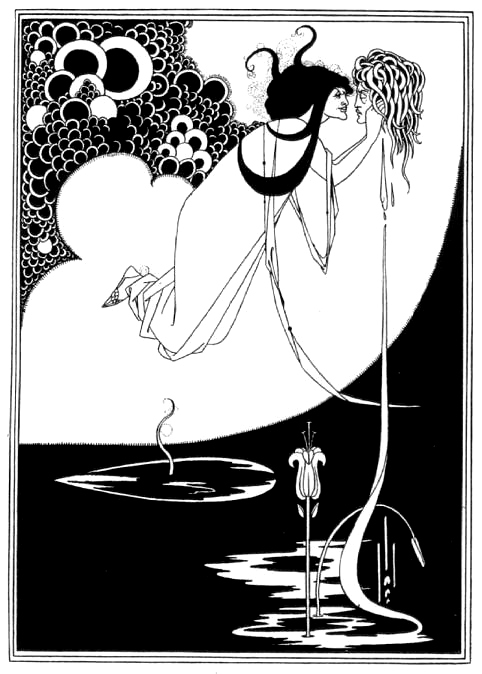

The Climax. [Click on image to enlarge it.]

Aubrey Beardsley produced thirteen main illustrations for the first English edition of Oscar Wilde's play Salomé that seemed calculated to cause outrage among the nineteenth-century audience. Click on the image above to see a larger version.

If late nineteenth-century England was so troubled by Oscar Wilde, it was because he brought into unity the two sides of its personality – the official and repressed – that were supposed never to meet.

Like other outsiders of his time and beyond, the Irishman was acutely attuned to everything most “high” about English culture: he could render the speech of its genteel classes more exquisitely than anyone else, and dwelt deeply on its most revered texts: Classical literature and the Bible. But he also refused to subscribe to the official idea of culture – that it should be socially constructive and redemptive. For him art – and indeed love – tapped into aspects of the human soul that remained obstinately dark and purposeless, and, in his aesthete’s view of things, art’s ultimate responsibility was to itself, in all this immense and troubling breadth, and not to some moralist’s idea of bright social purpose. This made him a disquieting figure, as if, for all his evident brilliance, he was disloyal to a fundamental and sacred truth. This was not helped by his Catholicism or, later on, the public revelations of his “socially unproductive” sexuality – though the fault in this latter case was of course not so much his sexuality as his failure, once again, to keep it under wraps.

Wilde’s play, Salomé, was a flashpoint of his troubled relationship with British society: written in French and first performed in Paris in 1896, the English translation was shown only in private on the other side of the Channel until a public ban was lifted in 1931. This tortuous journey reminds us of another thing about England at that time: it was much more ignorant of contemporary Parisian developments in the theory and practice of art than we have come to suppose.

Roger Fry’s 1910 exhibition “Manet and the Post-Impressionists” was the first time London really saw what had been going on in French art for the last forty years: Virginia Woolf later said of its impact, “On or about December, 1910, human character changed.” And in some ways what England disliked in Wilde’s writing was its Frenchness– for he spent much of his time in Paris, and had absorbed from there a much more insubordinate idea of art’s relationship to society. The several, increasingly dangerous, nineteenth-century French treatments of the Salomé story, in literature and art, were less known to the British majority than to Wilde himself, and the perversion evident in his play burst upon London as if without precedent.

There is no doubt that Wilde’s version of the eponymous Biblical dancer made her into something new and even more terrifying than her French antecedents. In an overripe court awash with promiscuity of all kinds, her sudden erotic fixation on the filthy figure of John the Baptist, whose denunciations of lust and invocations of hell rise up stridently from his unseen dungeon, is already perverse in the extreme; her decision, when he refuses her amorous advances, to demand his severed head so she might kiss him all the same, is positively psychopathic.

All the same, there is something repetitive and mannered about Wilde’s text that can make it stilted, even tedious, for today’s reader. In some ways, Wilde’s view of art and the soul has become so fully our own that it is difficult to recapture the scandal that he represented to his contemporaries. Merely gesturing to the perverted energies at work in society’s official stories no longer surprises us, for we think it is art’s job to do precisely this: we no longer look to it for chaste moral instruction. After Wilde, Freud demonstrated the connections between humans’ highest and basest drives, and the most determinedly sublime of all nineteenth-century European cultures – the German – was turned upside-down by the most terrifying outpouring of principled depravity – and since then we have come to feel there is actually something healthy and normal about naming the beast within.

Because of this, it is more in the passionate creative responses to Salomé than in the play itself that we can feel again, today, the outrage it represented. One of the greatest of these was the opera setting by Richard Strauss (1905), which put Classical symphonies and courtly dances into a morbid echo chamber and so produced a sound that greatly expanded the power and contemporary relevance of Wilde’s sense of putrefaction at the heart of “civilisation”. But the other is the illustrations to the play by Wilde’s English acquaintance Aubrey Beardsley.

A strange and complex man, Beardsley died of tuberculosis aged twenty-five, and his reputation is based on just about five years of work, most of which was literary illustration. Another Francophile, Beardsley’s artistic style had its origins in the encounters he had in Paris with illustrators such as Toulouse Lautrec, and with the Japanese prints – especially erotic – so much in vogue there in the 1890s.

Though his figures often bore physiognomic resemblances to those painted by contemporary English Pre-Raphaelites such as Edward Burne-Jones, in his imaginings they are released from any kind of naturalistic setting and plunged into unsettling dreamscapes peopled with shrunken dwarfs, priapic androgynes and drooping phallic flowers. The droop is significant, as are all Beardsley’s strange signatures – the wizened foetus, which represented his sense of his own premature – because of tuberculosis – age, and the Japanese-style artist’s stamp, which seems to show semen dripping from a flaccid penis – for Beardsley had no easily discernible sexuality, and seemed in his plates always to be watching the world of human arousal from a position of impotent exteriority.

As with Strauss’s music, Beardsley borrows, for his illustrations of Salomé, many of the tropes of established European art – cherubs, candelabras, and fine textiles – and, more specifically, much of the furniture of Watteau’s bucolic eighteenth-century depictions of fêtes galantes – lute players, masked Venetian revellers, marble statues in the woods – but he presses them into the service of a terrible counter-energy. The picture of Salomé looking into the face of John the Baptist after she has kissed his decapitated head is, unlike Wilde’s prose, as unsettling today as when it was first published.

Why does she float above this inky lake, and what is the scaly background? Is that blood or brain that oozes from the head in imitation of Salomé’s drapery, to be lost in the black nothingness below? Is it John’s own failing genitalia we are supposed to imagine at the base of his upright non-body? – for what “normal” manhood, indeed, could stand before a female energy so terrible as this? It is a haunting and unforgettable masterpiece of illustration, whose ultimate genius lies, perhaps, in the fact that Beardsley elects not to depict the actual kiss but a moment just after, a bizarre and unsettling moment he has imagined for himself, where Salomé looks into the face of the dead head, apparently hoping to find there – so demented is his heroine – some rush of tenderness, some – any – emotional reaction to her savage embrace.

Last modified 4 September 2013