View of the Sutton Dwellings looking east down Cale Street, Chelsea, London SW3.. Photographs by George P. Landow 2011. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL or cite it in a print one. Click on the thumbnails below for larger images.]

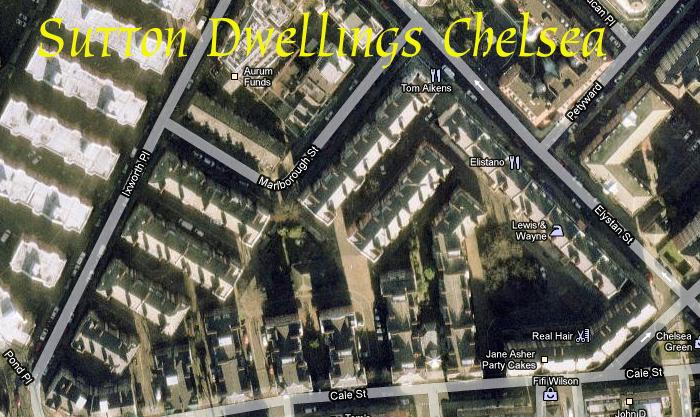

The layout of Sutton Dwellings Chelsea and their relation to the surroundings

The more than a dozen separate blocks of flats of varying lengths that constitute Sutton Dwellings occupy a plot of land shaped roughly like a W with a line drawn across the top bordered by Elystan, Cale, Ixworth, and Marlborough Streets. The longest single building, which contains an archway entrance into a courtyard, parallels Elystan Street. Another shorter one divides into two halves that meet at a slight angle, one of which faces a small irregular square, Chelsea Green, on Elystan Place and another that runs parallel to Cale Street while 6 others sit perpendicular to Cale Street; another 4 are perpendicular to Ixworth Street with the long side of one facing Marlborough Street. [See the image below based on Google Maps.]

The Socio-political Significance of the Sutton Dwellings

The Sutton Dwellings Trust exemplifies a late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century situation that still occurs today: the collision of philanthropy, classism, the need for housing the poor, city planning, and fierce local resistance of the wealthy to having the poor live anywhere near them. Archives in London and the M25 Area explains that William Richard Sutton "ran a carrier business from Golden Lane, Finsbury and built up a huge personal fortune through wise investments and business expansion. When he died in 1900, he left £1,500,000 for the provision of model low-rented dwellings for occupation by the poor of London and other towns and populous places.” That £1,500,000 probaby had the purchasing and political power of £150,000,000 today. Patricia L. Garside, who describes the Sutton Model Dwellings Trust as "the wealthiest housing trust in England,” argues that a major reason this generally successful philanthropic enterprise managed to "build comparatively few dwellings before 1939” lay in the strategies of the rich and powerful, who used every resource available to contain "the potentially disruptive features of the trust,” and these strategies involved "the courts, the Attorney General, and central and local government.” Nonetheless, the Trust's funds, determination, and lawyers managed to build handsome, successful housing that has lasted to the present day in London and other parts of the U. K.

(a) Front view of one of the apartment blocks perpendicular to Cale Avenue. The archway entrance to the courtyard from Elystan Street is out of sight at the right. (b) An entrance on Cale Avenue to one of the units. (c) Rear view of one of the apartment blocks perpendicular to Cale Avenue.

Fierce resistance delayed construction of much-needed housing for the poor, and "the first dwellings in Bethnal Green (at Sceptre Road and Coventry Road) were not built until 1909. Later London schemes were at City Road and Old Street (1911); Chelsea (Cale Street and Elystan Street, 1913); Rotherhithe (Plough Way and Chilton Grove, 1916); Islington (Upper Street, 1926) and St Quintin Park, North Kensington (1930).”

The trust built both groups of 5-storey apartment blacks, such as we see in Chelsea, and semi-detatched homes in Birmingham. A History of Birmingham Places & Placenames, a website that has a section on the semi-detatched housing, explains "By World War 2 the Trust was housing over 30,000 people, and by the end of the 20th century the William Sutton Trust had built or bought some 14,500 houses and flats in 33 towns across the country. A strong emphasis of the Trust is to foster community interaction on their estates.”

Two views from Cale Street showing the how the blocks meet each other at varying angles.

Left to right: (a) and (b) Two entrances to the housing complex, (c) A roofline much like those found on nearby blocks for wealtheir Londoners constructed in the Pont Street Dutch and other styles created by Norman Shaw.

After examining the history of the Trust, Garside argues several points, the first of which is that the "the rise of council housing cannot be explained by the inadequacy of philanthropy,” the second that evidence proves "as early as 1906, the Local Government Board was using a variety of financial and legal devices to prevent local authorities from facilitating the work of the potentially powerful Sutton Model Dwellings Trust.” Looking at the Sutton Dwellings in Chelsea suggests an additional point of some importance: the housing created by such philanthropic trusts turns out — in both architectural and human terms — to be far more successful that most later council housing. These buildings fit in very well with the Norman Shaw-built and inspired buildings of Chelsea and Kensington.

Bibliography

Garside, Patricia L. "The Impact of Philanthropy: housing provision and the Sutton Model Dwellings Trust, 1900-1939." Economic History Review 53:4 (2000): 742-66.

Phillips, E. M. Growing Old Gratefully. Illustrated by Roland Ungoed-Thomas and Shahid Malmood. London: William Sutton Trust, 1999.

"The Sutton Housing Trust.” Archives in London and the M25 Area. Web. 18 January 2011.

"The Sutton Estate.” A History of Birmingham Places & Placenames. Web. 18 January 2011.

Last modified 22 January 2011