Image capture by the author. [You can use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the source and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one. Click on the images for larger pictures.]

The model village of Port Sunlight on the Wirral peninsular in Cheshire was proposed and founded by William Hesketh Lever (1851-1925), later 1st Viscount Leverhulme, to house the workers at his Sunlight soap plant. Possibly the idea came to him from Titus Salt, whose model mill village, Saltaire, in Yorkshire was one of several such workers' communities planned by Victorian industrialists (see Curl 171). But there were other precedents, including one much closer at hand: Price's Candles had built (and was still enlarging) a village for its workers just on the other side of Bromborough Pool, where Port Sunlight was to have its own dock facilities (see Hartwell et al. 187-88). Whatever the immediate inspiration, the result was an attractive project later captured in a book by the architectural illustrator, journalist and editor, Thomas Raffles Davison, ARIBA (1853-1937). As his frontispiece Davison shows a girl reading a book in one of the many leafy spots there, with Port Sunlight's Christ Church in the background, clearly suggesting the enlightened and enlightening ethos of the place.

The first layout plan for Port Sunlight was by Lever himself, but it was refined by the Warrington architect William Owen (1849-1909), whom he had consulted about the site and who, together with his son Segar, designed the original factory, the first twenty-eight houses in about 1889-90 (see Hartwell et al. 530), and the Victoria Bridge in 1897, over the widest of several tidal creeks traversing the terrain. The bridge, named in honour of the Queen in her Diamond Jubilee year, and opened with some fanfare by the Premier of New South Wales, the Hon. George H. Reid, is still there but can no longer be seen: in about 1907 the "handsome" structure disappeared when the creek was filled in (Hartwell et al. 535).

Victoria Bridge, Port Sunlight, designed by Owen. On the left is Bridge Inn (1900), designed by another local partnership much involved here, Grayson & Ould of Liverpool. On the right is Owen's Christ Church. Source: George, facing p. 8.

Over the years, a number of other local architects would be involved in the project as well, and a few nationally important ones would also be commissioned for particular buildings, but the original partnership went on to design many of the main public buildings, such as the first cultural venue, the Gladstone Theatre (1891), Hulme Hall, which was designed as a dining-room for women (1901), as well as Christ Church itself (interestingly, not until 1902-04). Built as a memorial to Lady Lever, the art gallery inevitably came later still, after William Owen's death, but this was also by the family firm (1914-21).

Plan for Port Sunlight model village. Source: Davison 36.

What is striking about the plan itself is the amount of land allocated for allotments and recreation. There were altogether ten allotment gardens. An early commentator writes, "the dells and the central portions of the building sections are ideally suited for allotments. It is now hardly necessary to defend the view that labour on the land is a healthful change for a man who is confined during the day within a factory, however well ventilated it may be. It may be said that he will be too tired to do much work in addition to his daily eight hours, but experience shows that rest is found in change rather than in idleness" (George 101), and indeed, these allotments proved very popular.

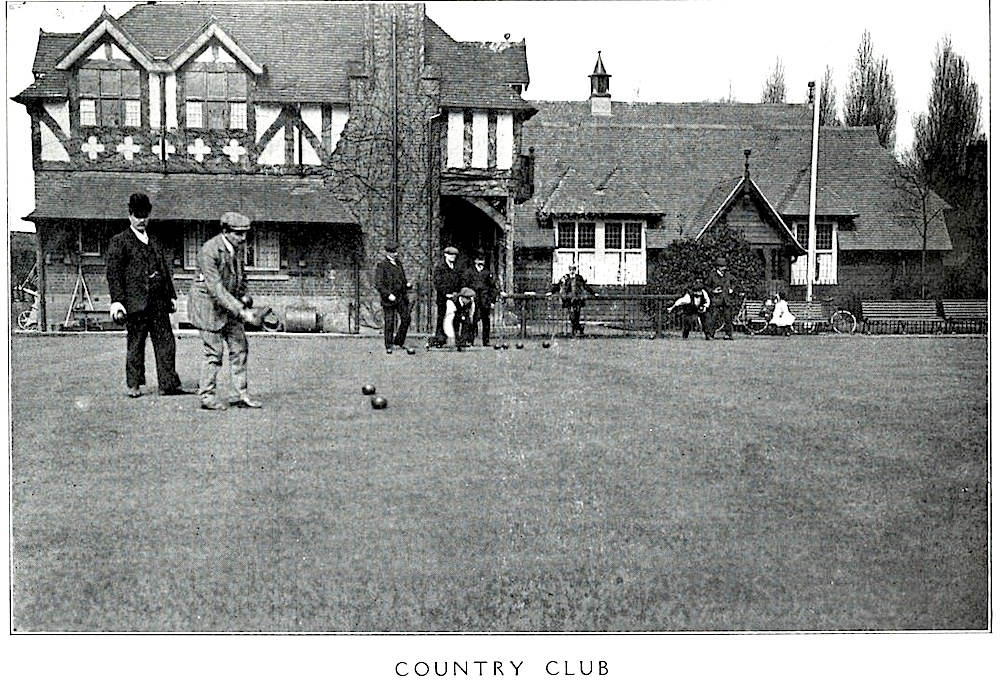

Villagers, including both cloth-capped and bowler-hatted men, on the bowling green by the clubhouse. Source: Beeson 28.

As for recreation grounds, there was a "positive embarrassment" of these and other social facilities (see Hartwell et al. 534). They included a football and cricket ground, another recreation ground, a tennis lawn, a bowling green, four further play areas, as well as wooded parkland near the works themselves, to the lower right of the plan. In 1902, William & Segar Owen added a gymnasium and an open-air swimming pool. The idea was to produce healthy and happy employees, and to promote harmony across the whole workforce. For social cohesion, in particular, there was also a club, where employees of every level could meet and mingle: "it shows that men in different positions can mix successfully, and be drawn together for their mutual benefit," says Edward Beeson (126). Tellingly, Davison refers to it as the "Co-Partners' Club" (6).

Unlike Saltaire, Port Sunlight did have its inn: Bridge Inn at the end of Victoria Bridge, shown above. However, that was the only one, and it had been set up originally as a Temperance Inn with no alcoholic beverages on sale. Lever had soon had to accede to requests for it to be licensed (see Hubbard and Shippobottom 35), but it still seems to have had something of its original air about it: "though fitted with a bar and a smoking-room," writes George firmly in 1909, it is "really a restaurant." Suggesting that there were many more improving ways for the villagers to spend their time, George makes a point of describing its "deserted condition" in the evenings (115). It was not until 1981 that it was actually leased to a brewery company (Hubbard and Shippobottom 35).

A bird's eye view of Port Sunlight in 1914. Source: Davison, Plate 1, following the List of Illustrations.

In some ways, the site had not been a very promising one, containing "a number of ravines filled with slime and ooze" (Curl 171) besides the creek under Victoria Bridge, but this in itself encouraged the setting aside of areas of open ground. Around and even within the residential roads, there was a sense of space: "The Port Sunlight secret lies in the tree and the shrub, but still more in the broad meadow; the houses are generally built on one side of the road only and overlook broad spaces of grass or belts of trees. This increases the feeling of privacy a feeling which has its moral value so long as it is not allowed to destroy the social spirit" (George 71). As so often "moral value" and "social spirit" are emphasized.

It is easy to be cynical about the provision of good living conditions for employees as a sound investment for future growth, and to decry Lord Leverhulme's paternalistic attitude as a form of control. But there was certainly an element of idealism. Like Sir Titus Salt, he believed in sharing the profits of labour with the workers. What is more, apparently, "heavy subsidisation was necessary" (Tarn 160). We might therefore see why Davison was so taken with the project: "The last and best word we can say about the village of Port Sunlight is that the aim of its founder has been based on the belief that sympathy for the wants and well-being of our fellow-men may find a large expression even in our business dealings" (vii).

Related Material

- Port Sunlight: Housing

- Port Sunlight: Amenities

- Christ Church, Port Sunlight

- Lady Lever Art Gallery, Port Sunlight

- The tombs of Lord Leverhulme and his wife in the loggia of Christ Church, Port Sunlight

- The Defence of the Home War Memorial at Port Sunlight

- The Leverhulme Memorial at Port Sunlight

Sources

Beeson, Edward William. Port Sunlight, the Model Village of England: A Collection of Photographs by Edward Beeson. New York: The Architectural Book Publishing Company, 1911. Internet Archive. Web. 1 September 2013.

Curl, James Stevens. Victorian Architecture. Newton Abbot: David & Charles, 1990.

Davison, T. Raffles. Port Sunlight: A Record of its Artistic & Pictorial Aspect. London: Batsford, 1916. Internet Archive. Web. 1 September 2013.

George, Walter Lionel. Labour and Housing at Port Sunlight. London: Alston Rivers, 1909. Internet Archive. Web. 1 September 2013.

Hartwell, Clare, Matthew Hyde, Edward Hubbard and Nikolaus Pevsner. Cheshire. The Buildings of England series. New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 2011.

Hubbard, Edward, and Michael Shippobottom. A Guide to Port Sunlight: Including Two Tours of the Village. Rev. ed. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 1996.

Tarn, John Nelson. Five Per Cent Philanthropy: An Account of Housing in Urban Areas between 1840 and 1914. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1973.

"Thomas Raffles Davison." DSA (Dictionary of Scottish Architects). Web. 1 September 2013.

"Victoria Bridge Stones." PMSA (Public Monuments and Sculpture Association). Web. 1 September 2013.

Last modified 1 September 2013