City Wall, New College Gardens, Oxford. Drawn by W. Matthison. c. 1909. Source: Artistic Colored Views of Oxford. Click on images to enlarge them.

WILLIAM OF WYKEHAM, the famous founder of New College’ began life as a carpenter’s son, and ended it as Lord High Chancellor of England and Bishop of Winchester. In the days of his prosperity he bethought himself of ‘the struggles of his youth’ and ‘desiring to help other poor and ambitious boys’ determined to found a school in his native town of Winchester’ and a college at Oxford’ to which the Winchester boys might go when they arrived at the age of fifteen. His choice of a site at Oxford was a piece of land bounded by the city wall, which ‘having been used as a plague pit’ and subsequently left unoccupied’ had become a public nuisance, “full of filth’ dirt and stinking carcasses,” the gathering place of “malefactors’ murderers’ whores and thieves’ to the great damage of the town and danger of scholars and other men passing that way.” Wykeham’ squick brain had instantly grasped the advantages of its position, and when he had added some gardens and a few old halls he found himself in posses sion of sufficient ground for his purpose’ and proceeded to erect the magnificent structure which, “almost unchanged” confronts the visitor to-day. He called it “Saynte Marie College of Winchester,” but as there was already a college of that name (afterwards changed to Oriel) it was generally known as the New College.

At nine o’ clock on the morning of Palm Sunday, 1387, with litany and solemn procession’ the Warden and scholars passed under the gateway and took possession of their habitation; chapel and hall, library, treasury, cloisters, warden’s house, lodgings for the scholars, and various domestic offices were all there’ just as they stand at the present day’ except for a few small additions and alterations hereafter noted. No college then in existence could boast a tower gateway, warden’s house, cloister, cemetery, or regular library, nor was there another chapel composed simply of choir transepts, but many later founders copied Wykeham’s model, and undoubtedly his work hastened the transition between the Decorated style of architecture and the Perpendicular.

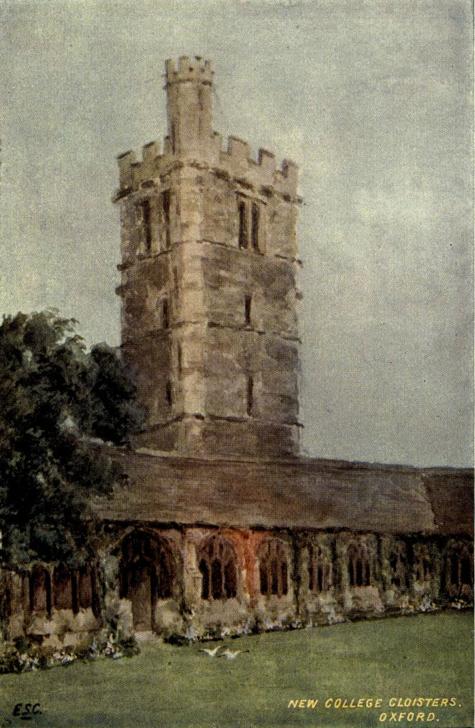

Left: View from Cloisters. W. Matthison. c. 1909. Source: Artistic Colored Views of Oxford . Right: New College Cloisters. Signed “E.S.C.” Source: Artistic Colored Views of Oxford.

The statutes drawn up by Wykeham for the govern ance of his college were based upon the famous “rule of Merton,” but with far more detail, covering indeed a hundred and seventeen printed pages, his intention being to keep out every abuse wont to creep into such communities. The foundation consisted of a warden and seventy “poor and indigent scholars, having the first clerical tonsure, adorned with good manners and of good condition, sufficiently instructed in grammar, honest of conversation, able and fit to study and desirous of advancing in study.” The position of warden was one of unusual importance and dignity. He lived in a separate house, took his meals in a hall of his own, kept a cook who occasionally dined with the fellows, and had six horses on which to mount his attendants when he went forth to collect moneys due to the college. Daily chapel was a new institution in Oxford, and so were the tutors, who supervised the studies of each scholar for the first three years, receiving in return a shilling a week for food and an annual suit of clothes, which it was expressly stipulated they were neither to sell nor pawn, but might give away at the end of four years. The Bishop of Winchester was appointed visitor. Three times a year a solemn scrutiny was held for the purpose of inquiring into the daily life and work of the members of the college and each was urged to mention anything he had seen amiss in the conduct of the others, candid criticisms, even of the chaplain’s boots, frequently resulting.

New was a luxurious college according to the ideas of Wykeham’ s day. In the scholars’ lodgings the rooms on the ground floor’ with three windows’ had three occupants, and those above, four windows, four occupants. At each window there was an arrangement called a “study,” consisting of a desk, bookshelf, and a seat without a back. There was no glass in the windows, they were protected simply by a linen blind. There were no fires except in hall, nor covering to the floor save straw. In each room there was a fellow “more advanced than his chamber fellows in maturity, discretion and knowledge,” who acted as prefect and reported periodically to the warden. The beds were made and similar services performed by the choristers; no women were allowed in college, and if the soiled linen were sent to a washer woman she must be “of such age and condition that no sinister suspicion can, or ought to fall on her. ”Lectures in the schools began at six and went on till eight, when mass was said, after which work was resumed until dinner at eleven. The scholars retired to their “studies” immediately they had finished and at one o’clock lectures began again.

Only on great festivals were the scholars allowed to sit round the great brazier after dinner or supper and “indulge in, songs and other solaces or listen to poems, chronicles of the realm, wonders of this world or other things which befit the classical state.” This was the only recreation permitted by the founder. “Games of dice, chess, hazard or ball and every other noxious’ inordinate, unlawful and unhonest game” was forbidden. There was to be no “hurling or shooting of stones, balls, or other missiles within the college walls, no wrestling, dances, jigs, songs, shoutings, tumults or inordinate noises, effusions of water, beer or other liquor or tumultuous games in the Hall.” The scholars were to walk abroad two and two, and a special servant was to carry their big clasped books to the schools.

New largely realised its founder’s hopes in regard to the advancement of learning. Within its walls the Renaissance in Oxford - i.e. the revival of classical learning — was begun in the fifteenth century. Warden Chandler’s Latin prose in 1454 was better than any known in England since the twelfth century’ and Greek was taught here for the first time in England by the Italian’ Vitelli, one of whose pupils was the famous William Grocyn. Later on, however, it seemed as if the brilliant promise of the Wykehamists was to end in very small achievements, as Archbishop Laud remarked at the time of his great visitation’ and indeed a saying then current in Oxford’ “Golden scholars, silver Bachelors, leaden masters, wooden doctors,” referred in particular to New, “which,” Anthony Wood wrote,“ is attributed to the rich fellowships they have’ especially to their ease and good diet, in which I think they exceed any college else.” Still their scholarship was not wholly dead as was proved by the fact that three out of the four sub-delegates who drew up the Laudian Code were men from New; the warden, Dr Pincke, Dr James, and Dr Zouche. Dr Zouche was the most famous civilian of his time, and rose to great eminence’ while Dr James, the first librarian of the Bodleian, was perhaps the greatest scholar the college has ever produced.

The blaze of colour and rich ornament which Wykeham had lavished upon the interior decoration of his chapel were not permitted to remain after the Reformation. The images and side altars were first abolished, then followed Bishop Horne’s famous visitation, when the exquisite reredos and the stained-glass windows’ which had been the founder’s special pride, ruthlessly sacrificed and the high altar reduced to the level of the stalls. A plaster wall on which were inscribed some texts from Scripture was all that met the eye for many years in the once beautiful chancel. The brasses in the cloisters, commemorating former members of the college who lay buried there “were sacrilegiously conveyed away, “during the Civil War, in the confusion caused by the transformation of the tower and cloisters into a magazine, for [the] arms and furniture, bullets, gunpowder, etc.,” of the Royalist troops. The choir school were obliged to give up their quarters between the chapel and the cloisters, and betake themselves to “a dark, nasty room, very unfit for such a purpose, which made the scholars complaine very much,” as the most industrious of Oxford historians, Anthony Wood, records, he being a small boy of eleven in the choir school at the time. He adds that when the university train bands started drilling in the quad, “there was no holding the scholars in their school... from seeing and following them.... Some of them were so besotted with the training and activities and gayities therein of some young scholars that they could never be brought to their work again.”

At the Restoration, when the love of art and beauty sprang up again, more vigorous than ever on account of its long repression, the chapel was redecorated and repaved. The memorial brasses which had formed part of its treasures were brought out from their place of concealment and placed in the north transept of the ante-chapel, where they still are; the most beautiful being those of William Hautryve (1441), Warden Cranley (1417), and Warden John Rede (1521). The stained-glass windows condemned by austere Bishop Horne were also brought out and put up in the antechapel, and now form the best collection of fourteenth century glass in this country. The west window alone belongs to a later date, having been put up in 1784, after a design by Sir Joshua Reynolds. It was at the Restoration too that a third storey was added to the college and the second quadrangle called the “Garden Court” was built for “noblemen and gentlemen not on the foundation” - i. e. gentlemen-commoners who paid handsomely for their accommodation

Links to Related Material

Bibliography

Artistic Colored Views of Oxford Being Proof Sheets of the Postcards of Oxford. Illustrated by W. G. Blackall. Oxford: E. Cross, nd. Internet Archive version of a copy in St. Michael's College Toronto. 3 October 2012.Lang, Elsie M. The Oxford Colleges. London: T. Werner. HathiTrust online version of a copy in the University of Michigan Library. Web. 8 November 2022.

Last modified 11 November 2022