Colour photographs by the author, who also downloaded the line drawings from the Internet Archive. You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer or source and (2) link your document to this URL. Click on the images to enlarge them.

Schinkel's early life

Marble statue of a youthful-looking Schinkel by Friedrich Drake (1805-1882), 1860, in the National Gallery, Berlin.

As state architect of Prussia in the early nineteenth century, Karl Friedrich Schinkel (1781-1841) is best known for some of the grand public buildings that turned Berlin into one of the great cities of the world. What is less well known is the impetus given to his work by his travels abroad, including a tour of Britain — and the influence that he himself exerted here.

Schinkel was born in Neuruppin in the Brandenberg Magravate. He was only six years old when his father, a church minister with responsibility for the local churches and schools, lost his life fighting the terrible fire of 1787 that destroyed the family home, along with most of the town. Schinkel's mother and her young children moved into housing provided for ministers' widows, and from that point the boy grew up watching Neuruppin being rebuilt around him. It was planned on rational principles under the auspices of Friedrich Wilhem II, and the experience of watching the town spring up again can be seen as one of the major inspirations for his life's work (Schönneman 10).

In 1794 the family moved to Berlin, where Schinkel completed his education, becoming an admirer, student and soon close friend of the young neoclassical architect Friederich Gilly (1772-1800), with whom he lodged from 1799. An early commission from Queen Louise, Friedrich Wilhelm III's consort, gave a boost to Schinkel's career at a time when he was still working on stage or interior design; and eventually, after travels in Italy and a spell as a painter, he established himself in his true calling. He became the chief building surveyor for the government, and soon afterwards was appointed to a professorship at Berlin's Bauakademie, a position once held by Gilly, who had died of tuberculosis at the age of only 28.

Schinkel's career as an architect

Schinkel's vast and commanding neoclassical Konzerthaus (1818-21), Gendarmenmarkt, Berlin.

Two more of Schinkel's buildings in Berlin. Left: The Altes (Old) Museum (1823-30), another great neoclassical landmark, on Museum Island, Berlin. Right: The neo-Gothic Friedrichswerdersche Kirche (1824-31), seen from Schinkelplatz, later used as a museum for Schinkel's work. This was closed and cordoned off when last visited (the unsightly cordons have been digitally removed).

Schinkel's tour of Britain

From the earliest stages of his career, Schinkel was interested in developments elsewhere in Europe, and not just in Italy. The Friedrichswerdersche Kirche, for example, shows clear evidence of British models. In this case, the Crown Prince (the future Friedrich Wilhelm IV) had urged the young architect to read up on them (see Riemann 2). But then in 1826 Schinkel was sent to see Britain for himself, partly on a mission to buy fashionable furniture for Prince Karl of Prussia (a younger brother of the Crown Prince), but more importantly on what has been called "a discreet spying trip" (Hill 68) to see work in progress at Robert Smirke's British Museum. In the event, he spent two months travelling around with his friend Peter Beuth, who was head of the Prussian Department of Trade and had been to Britain before, and together they took in Manchester, Birmingham and the Potteries, Scotland and North Wales, as well as London.

Beuth's main interest was on the industrial side, and it was industrial architecture that captured most of Schinkel's attention too. In Wales, for example, he sketched Telford's bridge at Conway, and his newly completed one over the Menai Straits, describing it in his journal as "a wonderful, daring work" (188). In Edinburgh, he was fascinated by Tanfield Gasworks: "We went to the gasworks which provide the town's lighting: an excellent plant," he wrote (156). When he saw the dreadful, monotonous housing for workers and the monstrous mills of Lancashire, he blanched at the perceived threat to the "art of building, and social peace within society" (Betthausen 7). Still, he was astonished by the new functional structures of the age, and they undoubtedly influenced his later work.

The more majestic of the urban landscapes caught his eye as well, to the extent that in Edinburgh he sketched panoramas of the city from different vantage-points. From Calton Hill he drew one that included William Henry Playfair's neoclassical Royal Scottish Academy, completed that very year, standing in splendid isolation on Princes Street, with no Scott Monument in the foreground yet — that would not come till the 1840s. In London he was struck not only by "joists ... of wood with iron" (The English Journey, 86) and so on at the docks, but by John Nash's projects, including the "village complexes" as Heinz Schönemann terms them (11), at Regent's Park. Work had started on the Park Village East houses there in 1824. All this certainly made an impact on him as well. He called in on both Cockerell and Nash, although unfortunately neither was at home at the time.

Schinkel's later career

Bronze statue of Schinkel by Drake, 1869, in Schinkelplatz, Berlin. Less youthful now, the architect looks dashing in his swirling cloak, and is still intently focussed on his architectural planning.

In his government capacity Schinkel was to be a major force in the development of Berlin into a capital city. Moreover, he was in charge of "projects in the Prussian territories from Rhineland in the west to Königsberg in the east" ("Karl Friedrich Schinkel"). Indeed, from 1831, as "Oberbaudirektor," and from 1836 as "Oberlandesbaudirektor," he oversaw building projects throughout Prussia. Town planning was one of his many roles. But he was a theoretician too, and his vision extended beyond these practicalities. Among his last projects were designs for two noble royal palaces, spectacular complexes intended for spectacular sites: the Acropolis in Athens, and Orianda overlooking the Crimean coast. These were never built but remain a testimony to his remarkable skill as a draughtsman and his scope and ambition as an architect. Schinkel's very heavy workload may well have contributed to his poor health, and he suffered a fatal stroke in 1841.

Schinkel was certainly the most influential German architect of the early nineteenth century, giving his name to the "Schinkel era" in his own country, and having a huge impact outside it. "As a universally active artist, he came to be regarded as the definitive authority on art and taste, not only in the then Kingdom of Prussia — but way beyond" says Martin Steffens (7).

Schinkel's influence in Britain

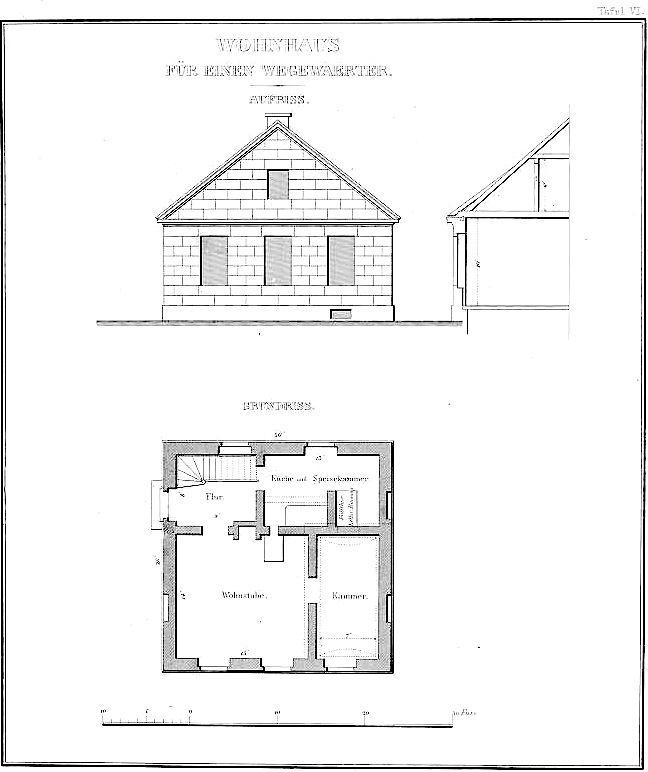

Plates at the back of Schinkel's Anweisung zum Bau und zur Unterhaltung der Kunststrassen, showing two of the "standard buildings" that he designed for highway keepers and toll collectors. Left: Plate V. Right: Plate VI.

Schinkel's designs were "much discussed" when C. R. Cockerell was teaching at the British Academy Schools (Brown 16). So, while it is impossible to stay in Berlin without coming across such impressive examples of Schinkel's work as the neoclassical Konzerthaus and Altes Museum, or the Friedrichswerdersche Kirche itself, it may be equally impossible to travel in Britain without seeing some buildings at least partially or arguably inspired by him. These range from important ones in which Cockerell himself had a hand, including St George's Hall, Liverpool, and the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, to the Albert Memorial, which may have taken something from Schinkel's set-designs for Hoffman's opera Undine (see Bayley 17). Intriguingly, his influence may even have extended to the humble and ubiquitous bungalow. This was introduced to Britain by Cockerell's student, John Taylor (1818-1884), in Westcliff-on-Sea in Kent, near Margate, and may owe something to Schinkel's plans for ordinary workingmen's cottages like those shown above.

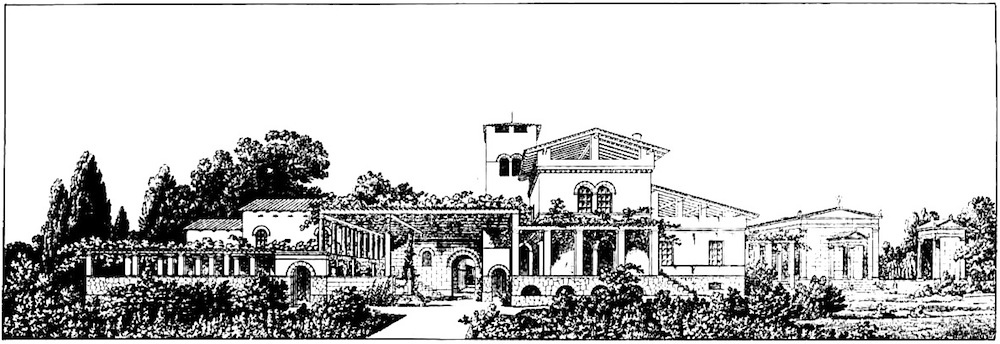

The Court Gardener's House at Charlottenhof, Potsdam, designed by Schinkel and built 1829-35. Source: Ziller 94.

It seems possible, then, that Schinkel gave back to Britain, particularly via Cockerell and later Taylor, some concepts that had previously impressed him here. As for the interesting case of the bungalow itself, he seems to have taken to our small country cottages from the very start: with their "bright window-panes, with white curtains behind," they were first buildings to catch his eye on arrival at Dover (The English Journey, 66). There are other hypotheses about the origin of the one-storey variety, of course. The most popular and indeed traditional one is that it derived not just its name but its form from living quarters on the sub-continent, called "bangla" in Hindi, which the British in Bengal adapted to their own needs. A recent alternative hypothesis, advanced by Andy Brown, is that the bungalow, despite the name it was given, did evolve from Schinkel, but from his more complex and picturesque Court Gardener's House of 1829-35 at Charlottenhof in Potsdam, a short distance from Berlin. This carries a certain symbolic significance: it has been taken as Schinkel's "blueprint for social harmony" (see Snodin 152-53). Most probably, here as elsewhere, various influences flowed together, and it may be hard to disentangle them.

Schinkel's connection with Britain was a fruitful one for him. It is pleasant to think that this important figure in world architecture — an idealistic and even visionary man, working under the constraints of his government role in his own country — left some mark, in turn, on our own built environment.

Related Material

Select Bibliography

Bayley, Steven. The Albert Memorial: The monument in Its Social and Architectural Context. London: Scolar Press, 1981.

Betthausen, Peter. "Karl Friedrich Schinkel: A Universal Man." Karl Friederich Schinkel: A Universal Man. Ed. Michael Snodin. New York & London: Yale University Press, 1991. 1-7.

Brown, Andy. "What's in a Name? The Origin of the British Bungalow." The Victorian. 53 (Nov. 2016): 12-16.

Hill, Rosemary. God's Architect: Pugin and the Building of Romantic Britain. London: Penguin, 2008.

"Karl Friedrich Schinkel." Art Directory. Web. 21 October 2016.

King, Anthony. "The Bungalow: An Indian Contribution to the West." The British Empire. Web. 21 October 2016.

Purver, Judith. "The Poet and the Princes: Eichendorff and the House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha." Crossing Frontiers: Cultural Exchange and Conflict: Papers in Honour of Malcolm Pender. Ed. Barbara Burns and Joy Charnley. Amsterdam and New York: Rodopi, 2010. 55-76.

Riemann, Gottfried. "The 1826 Journey and Its Place in Schinkel's Career." The English Journey: Journal of a Visit to France and Britain in 1826. Eds. David Bindman and Gottfried Riemann. Trans. F. Gayna Walls. New York & London: Yale University Press, 1993. 1-11.

Schinkel, Karl Friedrich. Anweisung zum Bau und zur Unterhaltung der Kunststrassen (Instructions for the construction and maintenance of new roads), with engravings by J. Willmore after designs by Karl Friedrich Schinkel. Berlin, 1834. Internet Archive. Contributed by the Getty Research Institute. Web. 21 October 2016.

_____. The English Journey: Journal of a Visit to France and Britain in 1826. Eds. David Bindman and Gottfried Riemann. Trans. F. Gayna Walls. New York & London: Yale University Press, 1993.

Schönemann, Heinz. "Schinkel's Dream." Architectural Work Today. Ed. Hillert Ibbeken and Elke Blauert. Stuttgart & London: Axel Menges, 2002. 10-11 (in German and English).

Steffens, Martin. K. F. Schinkel: An Architect in the Service of Beauty. Köln: Taschen, 2003.

Ziller, Hermann. Schinkel. Bielefeld, Leipzig: Velhagen & Klasing, 1897. Internet Archive. Contributed by Harvard University (in German). Web. 21 October 2016.

Last modified 31 October 2023