Simla as a Summer Capital

he Hill Stations of India, a colonial British contribution, were generally seen, as Dane Kennedy puts it,"as places where the British went to play" (1). They were summer resorts where during the hot weather, the higher echelons of the Government of India retreated to beat the harsh hot season of the Indian plains, to govern their Indian subjects from a distance, in climes and surroundings closely resembling the home country. How much time was actually spent in the business of governance and how much in private pleasures was difficult to determine. Certainly the inaccessibility of these locations to Indians in general and the British business communities of Calcutta and Madras were plus points. The issue of these "annual migrations to the hills" (Dane 216) stirred up much controversy and eventually led to questions raised by the Secretary of State and Parliament about their financial and political costs.

he Hill Stations of India, a colonial British contribution, were generally seen, as Dane Kennedy puts it,"as places where the British went to play" (1). They were summer resorts where during the hot weather, the higher echelons of the Government of India retreated to beat the harsh hot season of the Indian plains, to govern their Indian subjects from a distance, in climes and surroundings closely resembling the home country. How much time was actually spent in the business of governance and how much in private pleasures was difficult to determine. Certainly the inaccessibility of these locations to Indians in general and the British business communities of Calcutta and Madras were plus points. The issue of these "annual migrations to the hills" (Dane 216) stirred up much controversy and eventually led to questions raised by the Secretary of State and Parliament about their financial and political costs.

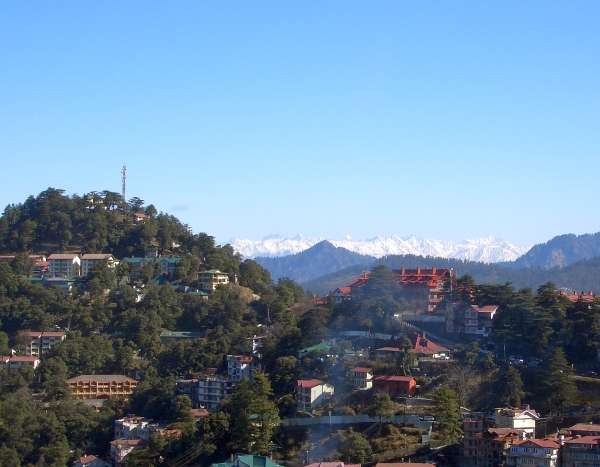

Simla's situation in the Himalayan foothills: Left: View towards the pine-clad valley. Right: View towards the Himalayas.

In the late 19th century, Simla had come to be designated as the summer capital of British India. Viceroys and their Councils spent at least twice as many months in Simla as they did in Calcutta, then the capital of the Raj. What the town lacked was a residence suitable for the status of a Viceroy. Previous Governor Generals and Viceroys used to lease private homes for their stay in Simla, including the mock Tudor "Peterhof", whose first occupant was James Bruce, Earl of Elgin. "Peterhof" subsequently served as the Punjab High Court and still later as the official residence of the Governor of Himachal. Today it is a 5-star hotel.

The New Viceregal Lodge

The new Viceregal Lodge, completed 1888, by Henry Irwin and his engineer associates.

The situation was corrected after 1884 by the new incumbent, Frederick Hamilton Blackwood, 1st Marquess of Dufferin and Ava, who was appointed Viceroy of India that year. Dufferin worked closely with Henry Irwin, then Chief Superintendent of Works, Simla Circle, to ensure the new building was completed before he left India in 1888. The Viceroy himself took a personal and active interest in the construction of the building.He suggested the general plan and until the designs were completed continually examined and modified the drawings in detail. He visited the construction site every morning and evening sometimes to the discomfort of the Public Works Department. Although Henry Irwin was the Chief Superintendent of Works, with him were Executive Engineers Hebbert and St. Clair, and Assistant Engineers Macpherson and English. The three first named had their names inscribed on the front porch.

The house possessed one of the most commanding views of Simla and the neighbouring hills. It consisted of a main block of three stories with a kitchen wing at a slightly lower elevation so that from its north eastern side, including one of its corner towers, it had a lofty, somewhat forbidding appearance almost like an English medieval castle. That this rather grim-looking grey building which the Dufferins so eulogised was in fact a combination of Scottish baronial, Gothic Revival, and Jacobethan adorned with "balustrades, collonades, crenellations" (Wrathall), not to mention turrets and similar other features did not seem to matter much to the incumbents. The overall effect of the exterior was not very beautiful. Inside, Irwin employed some of the traditional features of the Jacobethan style like the traditional entrance hall parallel to the portico, the long galleries, the loggias facing the entrance hall, and of course the grand wooden open-well staircase, to recreate the impression of spatial grandeur.

The Marquess of Dufferin and Lady Dufferin in India

Dufferin's predecessor in office, Lord Ripon, had attempted certain reforms which alienated entrenched British political and economic interests while raising hopes of participation in the governance of the country, among educated Indians. Dufferin's role therefore was to try and steer a middle course between a disgruntled Anglo-India and educated Indians, particularly the princely representatives of a bygone feudal India. The period of his service in India was marked among other things by important political developments such as the annexation of Upper Burma (1885-86) and mitigating the threat of a Russian invasion of Afghanistan. The first meeting of the All India Congress also took place at this time, in 1885. Despite his watchfulness of influential figures like Alan Octavian Hume in nationalist circles Dufferin preferred to remain publicly silent until very nearly the end of his Governor Generalship. On 30th November 1888 at a St. Andrews Day dinner in Calcutta, a few weeks before leaving India he delivered a speech attacking the pretensions of educated Indians whom he regarded as a "microscopic minority" of the Indian population (qtd. in Hardgrave and Kochanek 42). However he realised that the British administration in India would have to win moderate educated Indian support to survive.

Dufferin's wife, Lady Harriet Dufferin accompanied her husband on his travels in India and made her own name as a pioneer in the medical training of women in India. Her extensive travel writings and photographs in addition to her medical work challenged some traditional assumptions about the role of British women in colonial life. Excerpts from her diary with accompanying full blown illustrations — some of them quite rare like the original silk scroll presented to the Dufferins in Rangoon, 1886, a handwritten letter by Dufferin and photographs of the Marchioness on horseback from the now extinct firm of Bourne and Shepherd of Calcutta and Simla — show aspects of life in India and Burma during Dufferin's Viceroyalty and provide a delightful, if somewhat rarefied window into aspects of a Vicereine's life during the Raj. Among others they contain anecdotes about the Dufferins' arrival in India, their servants, the Viceroy's houses at Calcutta, Barrackpore and Simla, native entertainment including descriptions of a typical "nautch" and visits to the zenana. In addition, Lady Dufferin's impressions of Simla in its various aspects, their travels to Delhi, Agra and Rajasthan, Lucknow, after the Uprising, the king of Awadh's gardens, Burma and Madras and accounts of various meetings with the rulers of India's Princely states and the Burmese King Thibaw, lend interesting perspectives to a period of Colonial India's history, now largely forgotten.

Lady Dufferin's Journal Entries on Simla: On her Visit to the Inadequate Peterhof

Peterhof as it is today (it looked very different before its "makeover," although the situation is very much as Lady Dufferin describes it).

In April 1885, concluding a visit to Rawalpindi and Lahore, Lady Dufferin visited Simla and stayed at Peterhof for the first time with her husband. Her impressions, "greatly tempered by the consideration that it is to be our home for the greater part of the year" are reproduced below for interest. The account also gives a vivid description of the road to Simla:

We breakfasted early, and then started off on our long eight hour drive — D. and I in one "victoria," the girls in another, and the rest of our party in much less comfortable machines called tongas. Yesterday was lovely and we saw the mountains looking their very best.

We went at a great pace, ascending and descending, and twisting and turning round the most fearful corners, always at the edge of a precipice! Sometimes our road was exactly opposite to us, either very much higher or very much lower on the other side of a ravine; sometimes it seemed altogether lost, and was only to found again by pursuing it round some very sharp angle. There were patches of cultivation almost all the way up, culminating in beautiful and enormous rhododendron trees. For the rest the the scenery is that of a real sea of mountains, rolling hills of various heights, with snowy peaks in the distance, but no very striking range or particular peak to appeal to one's imagination. We changed horses every four miles, but even so our last pair seemed to feel the ascent to Government House very severely; indeed the road had become more precipitous and more angular than ever! [....]

The house itself is a cottage, and would be very suitable for any family desiring to lead a domestic and not an official life — so personally we are comfortable; but when I look around my small drawing room, and consider all the other dimunitive apartments, I do feel that it is very unfit for Viceregal establisment. Altogether it is the funniest place! At the back of the house you have about a yard to spare before you tumble down a precipice, and in front there is there is room for just one tennis court before you go over another. The A.D.C.s are all slipping off the hill in various little bungalows and go through most perilous adventures before coming to dinner. Walking, riding, driving, all seem to to me to be indulged in at the risk of one's life and even of unsafe roads there is a limited variety. I have three leading ideas on this subject of Simla at present. First I feel I have never been in such an out of the way place before; secondly, that I have never lived in such a small house; and thirdly I never saw a place so cramped in every way out of doors. I fear this last sensation will grow upon me. There is one drive which I tried to take yesterday, but had to turn back because of a thunderstorm.... [I: 130-31]

Lady Dufferin's Journal Entries on Simla: On her Visit to the New Viceregal Lodge

The rather forbidding approach to the Viceregal Lodge.

Three years later, on 15 July 1888, Lady Dufferin wrote about her first impressions of Simla's new Viceregal Lodge designed by Henry Irwin. It was commissioned just in time for the new Viceroy and his family to move in to their summer residence before saying their final goodbyes to this country:

I went up to the new house this afternoon and it did look lovely. It was Simla's most beautiful moments, between showers, when clouds and hills, and light and shade all combine to to produce the most glorious effects. One could have spent hours at the window of my unfurnished boudoir, looking out on the plains in the distance, with a great river flowing through; at the variously shaped hills in the foreground, brilliantly coloured in parts and softened down in others by the fleecy clouds floating over them or nestling in the valleys between them. The approaching sunset too made the horizon gorgeous with red and golden and pale-blue tints. The result of the whole was to make me feel that it is a great pity that we shall have so short a time to live in a house surrounded by such magnificent views.

The house too now that it approaches completion, looks so well and perhaps this is a good opportunity to give you some idea of it.

The entrance-hall is the great feature of it. The staircase goes up from it and there are stone pillars dividing it from a wide corridor leading to the state rooms and both hall and corridor are open to the top of the house three storeys.This gives an idea of space and height which is very grand. The corridor opens into the ball room with a large arch and a similar arch at one end of the ball-room, which is a lovely room furnished with gold and brown silks and with large bow-windows and a small tower recess off it. Sitting in it you look down the ball room the colouring of which is of a lighter yellow. It is a very fine room and outside the dancing space there is plenty of room for sitting as the wall is much broken up into pillars, leaving a sort of gallery round it. At one side in one of these spaces there are the large doors of the dining-room. It is a beautiful room. It has a high panelling of teak along the top of which are shields with the arms and coronets of all the Viceroys and of the most celebrated Governor-Generals, and above that Spanish leather in rich dark colours. The curtains are crimson. There is a small drawing-room furnished in blue. These are all on one side of the hall. On the other side is the Council-Room, the ADC's room, Private Secretary's office, etc.

Upstairs, the Viceroy's study and my boudoir are next to each other and my views are as I have said quite splendid. D's room is rather dark and serious looking. The colouring of mine is a bright sort of brown and it has a very large bow window and a tower-room recess which is all glass like the one in the drawing room. The girls will have a similar sitting room above me and all our bedrooms are equally nice.

The newest features of the house, as an Indian house, is the basement. "Offices" are almost unknown here and linen china plate and stores are accustomed to take their chance in verandahs or godowns of the roughest description. Now each has its own place and there is moreover a laundry in the house. How the dhobies will like it at first I don't know. What they are accustomed to is to squat on the brink of a cold stream and there to flog and batter our wretched garments against the hard stones until they think them clean. Now they will be condemned to warm water and soap, to mangles and ironing and drying rooms and they will probably think it all unnecessary and will perhaps faint with the heat. [II: 294-96]

On 23 July 1888 she again wrote

We really inhabit the new Viceregal Lodge today so I left the old directly after breakfast just returning there for an hour at lunch time and busied myself the whole day arranging my room and my things and the furniture in the drawing rooms. Happily the weather was very tolerable and our beds got here dry. D and the girls didn't come near the place till dinner time when everything was brilliantly lit by the electric light. It is certainly very good and the lighting up and putting out of the lamps is so simple that it it is a pleasure to go round one's room touching a button here and there and to experiment with varying amounts of light. After dinner we went down to look at the kitchen which is a splendid apartment with white tiles six feet high all round the walls looking so clean and bright. We sit in the smaller drawing room which is still a little stiff and company like but it will soon get into our ways and be more comfortable. [II: 298]

Electricity was unknown in Simla in the 1880s. Its introduction in the new Viceregal Lodge was a novelty and on the night of August 8th, the Dufferins entertained for the first time in the new house. "We had our first entertainment in our new house tonight," wrote Lady Dufferin:

It looked perfectly lovely and one could see that everyone was quite astonished at it and the softness of the light. First we had a large dinner — sixtysix people at one long table. The electric light is enough but as candelabras ornament the table we had some on it. At one end of the room there was a sideboard covered with gold plate and at the other end, double doors were open and across the ball room one one saw the band which played during dinner

We had all the Council and "personages" of Simla and the Minister, Asman Jah, from Hyderabad who brought his suite. After dinner people began to arrive for the dance. When not dancing, everyone was amused roaming about the new rooms, going upto the first floor whence they could look down on the party. [II: 298]

The Dufferins' Successors: Lord and Lady Curzon

The Ridge in Simla, showing its "hybrid" nature, with Christ Church and the Tudor-style Municipal Library (once a guest house).

More glimpses of the "little hybrid world" of Simla: Left: Shop fronts along the Mall. Right: The old bandstand (now a restaurant).

Ten years later, these expressions of admiration had changed to contempt. The Curzons were not particularly happy with the place. They disparaged the building with its mock baronial porches and its pseudo feudal towers and no less the Maples furniture inside. Both the Viceroy and his wife thought that the company at dinner "made them feel they were 'dining every day in the housekeeper's room with the butler and the lady's maid.' It got so bad that they took to camping in a field near the Simla Golf Course" (Ferguson 176). Subsequently they initiated many changes to the exterior and interior of the building. In 1916, Secretary of State, Montague, "thought it resembled a 'Scottish hydro' [an electric power house], while someone else compared it to 'Pentonville Prison'" (Bhatt 97)! According to another authority on English architecture the building bore a striking resemblance to Hardwick Hall in Northern England (e.g. see Joshi) where one of the three paramours of Queen Elizabeth I of England kept Mary Queen of Scots in "protective custody" before she was removed to Fotheringay in 1570 and executed. Edwin Lutyens too, was critical of Simla's hybrid architecture. Commenting on the mock Tudor houses in Simla generally, he is reported to have said, "If one was told that the monkeys had built it all one would have said, 'what wonderful monkeys, they must be shot in case they do it again!"(qtd. in Ridley 76). Indeed at one time a dozen men were apparently hired to keep the monkeys — a plentiful tribe even in today's Shimla — at bay from the Lodge's manicured lawns. Lutyens' sentiments have been echoed by post colonial British historians who were struck by Simla's "strange, little hybrid world — part Highlands, part Himalayas; part powerhouse, part playground" (Ferguson 151) — this last epithet based on Rudyard Kipling's surprise "that the Viceroy and his advisers should choose to spend half the year 'on the wrong side of an irresponsible river' ... cut off from those they governed" (qtd. in Ferguson 152), while officers of the Raj "sweltering in their sun baked outposts" who tried to hold the country together were freely "betrayed by their wicked wives up in the hills" (Ferguson 152).To return to the Lodge: this building, a mish-mash of styles, and not particularly original in concept, cost Rs 970,093 to build (Kennedy 164), an extravagant sum of money in the 1880s. Irwin designed and built many more public buildings in Simla, among them, the post-office, Army Headquarters, the Town Hall [incorporating the part that remains now, the Gaiety Theatre], The Railway Board Building [but not the one seen today, which was built 1896-97], Ripon Hospital and the Roman Catholic Church [St Michael's, shown to the right, below].

A Masterpiece of (Con)fusion

Indians loyal to the Raj would raise their eyebrows, but as Claire Wrathall a visitor from Britain pointed out in London's Finanacial Times some time ago, the fact remains that Irwin's masterpiece of (con)fusion — a view shared by the writer — was, in her opinion, "perhaps the ugliest building in India." An important consideration no doubt was that the locals had never seen or heard of Jacobethan or Elizabethan architecture before. It did not much matter to them what style was adopted and by whom, as long as it provided employment. Indeed it is significant that in the 19th century, there was a significant increase in the number of workmen employed for PWD projects not to speak of porterage and other services for British visitors to the hills. Much of this workforce was recruited from surrounding villages but retinues of khitmatgars, khansamas and ayahs [different kinds of domestic staff] also followed their masters so that they would be well looked after during the long summer season. There was large-scale exploitation both in terms of labour and wages. Some of the stone used in building the new Viceregal Lodge had to be carried manually, uphill and on foot, from quarries, some as far as 50 km away. In view of the fact that Indians were actively discouraged from visiting this most hallowed of British preserves — "[i]n 1902, Lord Curzon was outraged to learn that a Bengali zamindar [landowner] had purchased a house in Simla" (Dale 199) — the locals meekly accepted the new edifice as a monument to the British presence and the Colonial Government's intention to project its unconcealed superiority over an "inferior" race.

Henry Irwin and the Indo-Saracenic Movement Reconsidered

Created 26 January 2015