First photograph: a Library of Congress photomechanical print, slightly modified. Reproduction Number: LC-DIG-ppmsc-08097. Remaining photographs by the author, who also downloaded the scanned images. [You may use these without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer or source and (2) link your document to this URL. Click on them for larger pictures.]

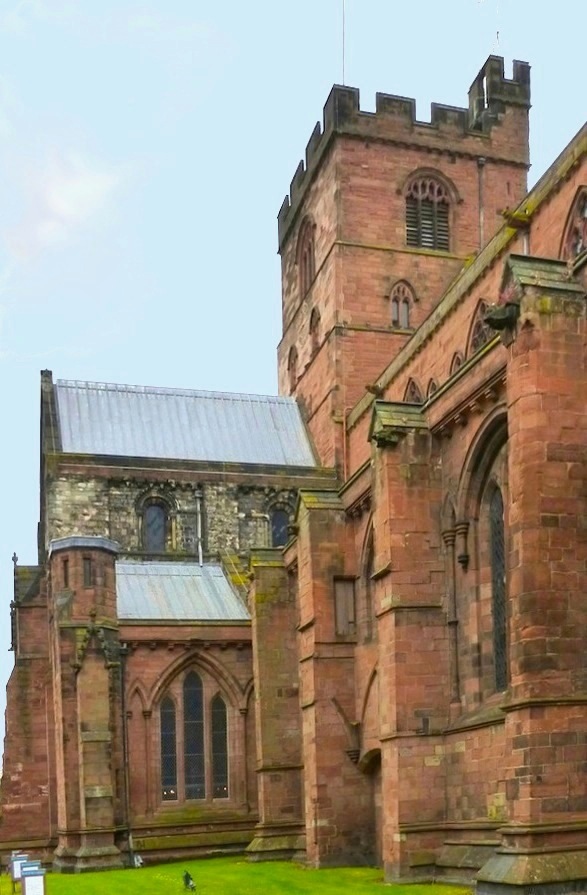

North-west view of Carlisle Cathedral as it was at the end of the nineteenth century.

Carlisle Cathedral, or the Cathedral Church of the Holy and Undivided Trinity, dates from the twelfth century and is one of England's eight old monastic cathedrals (see Pevsner and Metcalf 13). Close to the Scottish border, it "always remained remote and poor" (Lehmberg 273) and must have been in an interesting state of decay when Sir Walter Scott got married there in 1787. But it had some much admired features, and was quite radically restored by Ewan Christian (1814-95) in 1853-70. It is now Grade I listed.

Its earliest parts are of "mixed red and calciferous squared sandstone blocks" (listing text), while the rest is of red sandstone ashlar. At the time of the main Victorian restoration by Christian, Bishop Tait, who had been Dean of the cathedral when the work started, said,

I think I have heard some exclaim, as they look up to the old battered and cracked walls which rise over the new doorway, "Of course you do not mean to leave these rugged black stones in their deformity while all else is being renewed." Most certainly we do. To touch them would be sacrilege. Here is the Norman Church — within these walls the proud conquerors of England worshipped. [5]

The buttresses end in pinnacles, and it has parapets, battlements on the tower, and lead roofing, except to the the south transept, which is of copper (see listing text). The cathedral church is located in central Carlisle.

Ewan Christian's Restoration

Left to right: (a) Approach along the south side to the south transept and porch. (b) South porch entrance. (c) Ewan Christian's elaborately carved south doorway of 1856. (d) A heavy buttress, and the edge of an old monastic archway. Note the different building materials here.

Christian's contribution to what we see today was substantial, partly because so much of this cathedral had already been lost, and so much needed to be done to preserve the rest. "Rarely has it been the lot of a building to see such vicissitudes as this Cathedral has witnessed," wrote Christian's partner Charles Henry Purday, who supervised the restoration work. Summarising the effects of border hostilities, fire and civil war through the ages, he added significantly, "Even here the work of destruction did not stop; mistaken ideas of taste robbed it of many features of beauty and interest" (24).

Thus, the restoration undid some earlier work. For example, it returned the roofs of the nave and transepts to their original heights (see Hyde and Pevsner 225). But it did a lot of new work as well. In particular, because the foundation of the south wall had been disturbed when the remains of conventual buildings were removed, "massive buttresses were added, and a very richly sculptured doorway inserted between them," the latter making a fitting main entrance. Though judged by some to be rather "out of keeping with this distinctively Norman portion of the building" (Eley 21), the new doorway in the Decorated style was designed to harmonise with the most impressive and best-preserved part of the cathedral, the Early English and Decorated choir, rather than with what was left of its nave.

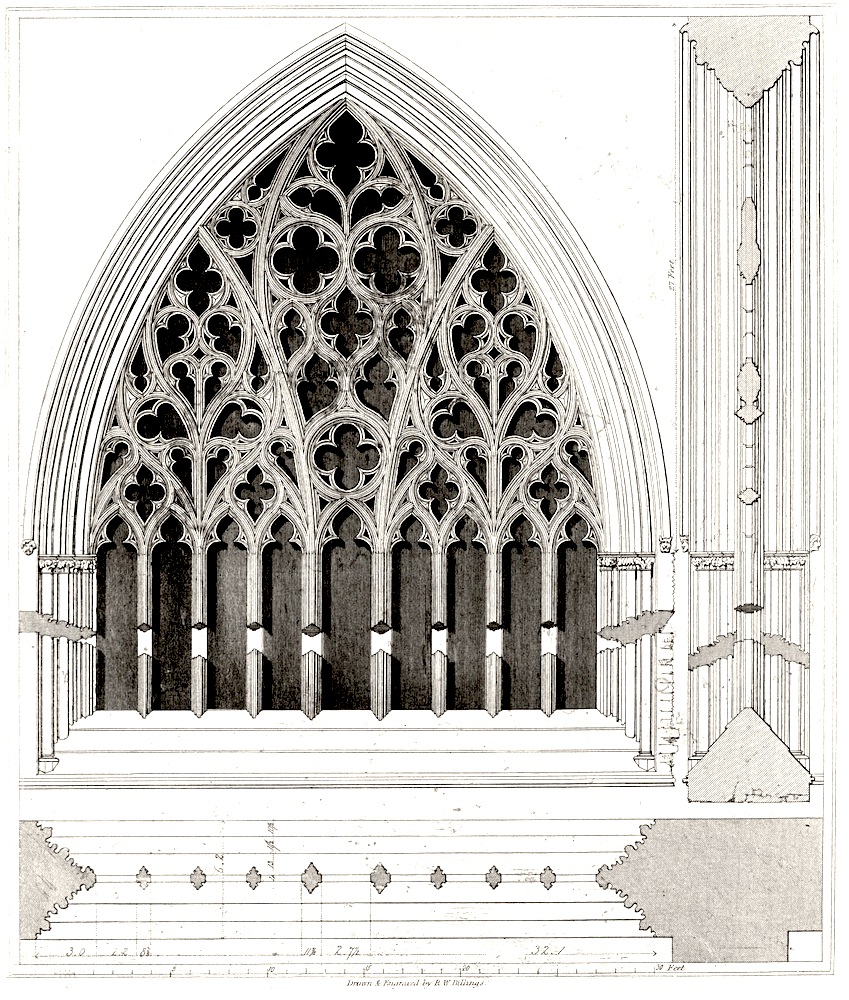

East elevation, oddly asymmetrical, but with the great east window: "a nine-light affair with the most resourceful flowing tracery" (Pevsner 20).

The east elevation too was in need of attention. A guidebook of 1840 mentions that "[t]he gable, which is not centrically placed, has crockets and crosses, now mostly broken off" (Jefferson 48). Nothing much could be done about the asymmetry, which was the outcome of the cathedral's chequered past, and serves as a clue to further asymmetry within: this is a quirky building altogether. But the gable, between the heavy buttressing to the south and a staircase tower to the north, could be smartened up, and life-size statues of St Peter, Saint Paul, Saint John and Saint James inserted in the empty niches (see Chesworth; these four were removed several years ago for conservation, though another one can still be seen, below the window in the apex). The main concern here, however, was the great east window itself, an amazing work of art, rightly celebrated for its Decorated tracery in an unparalleled curvilinear design. Like the painted roof of the choir, it is one of the special glories of this small, truncated cathedral. It dates originally from a rebuilding at the end of the thirteenth century. The arch mullions were added around the mid-fourteenth, followed later in that century by the tracery. But, again in 1840, Thomas Rickman described the window too as "considerably decayed" (qtd. in Billings 59). No wonder, perhaps, since Eley says that "[t]he mouldings were left unfinished until the restoration of the cathedral, 1856" (47).

Left to right: East window elevation, section and plan. Source: Billings, plate XIX. (b) The east window interior now, with baldacchino, high altar and reredos in front of it, the work of Sir Charles Nicholson. (c) View through the choir as it was in the late nineteenth century, illustrated by Alexander Ansted. Source: Ferguson, facing p.52.

Apart from work on the mouldings, preserving and refitting the precious medieval glass at the top would have been a monumental task. The tracery alone called for 86 pieces, some between 4' and 5' long. As for the nine lower panels, these needed new stained glass. In all, 263 pieces were involved for the 51' high window (Billings 63; Eley 46). It is hard to imagine the scale and delicacy of such an operation. But the result, as suggested above, was "Carlisle Cathedral's pride" (Pepin 49) — the whole window restored to its former glory, as we see it today from inside the cathedral. William Wailes was responsible for restoring the packed and vibrant scenes in the fourteenth-century glass of the uppermost part, showing Christ in Majesty presiding over the Last Judgement in graphic detail (1856), while John Hardman Powell of the Hardman firm provided the nineteenth century replacements below in 1859-61, these showing, less individualistically but perhaps more movingly, the life and ascension of Christ (see Hyde and Pevsner 233).

Roof painted to Owen Jones' design in 1856, looking from the choir to the crossing. The tall Gothic spire of the Bishop's throne can be seen on the left. The arch at the end is indeed off-centre: "crossing arch and organ pipes are jammed to one side of a blank expanse of battered stonework" (Hyde and Pevsner 229), the extra length of wall having been needed to accommodate the widening of the choir.

This is the other great feature of the Cathedral that Christian's restoration successfully rescued. The barrel roof was originally painted, but had later been hidden by a plaster vault. When this was removed in the Victorian restoration, the exposed wood was repainted in a similar way. The cathedral's own website explains, "the style we see of the restoration followed the medieval original, but the detailed design and colour of the ceiling with the angles and stars was the work of Owen Jones (1809-74), who was one of the great decorative artists of the day. It was last repainted in 1970." When the rather austere Bishop Close saw the work, he is said to have "solemnly ejaculated, 'Oh my stars!'" (Eley 45).

G. E. Street's Work

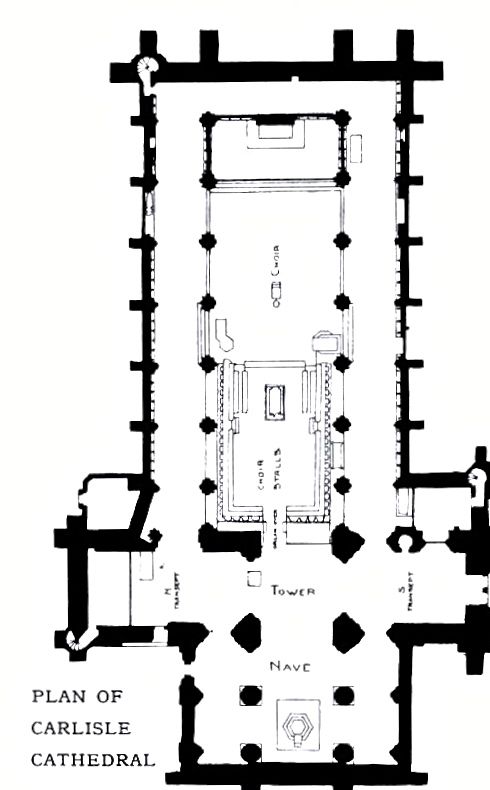

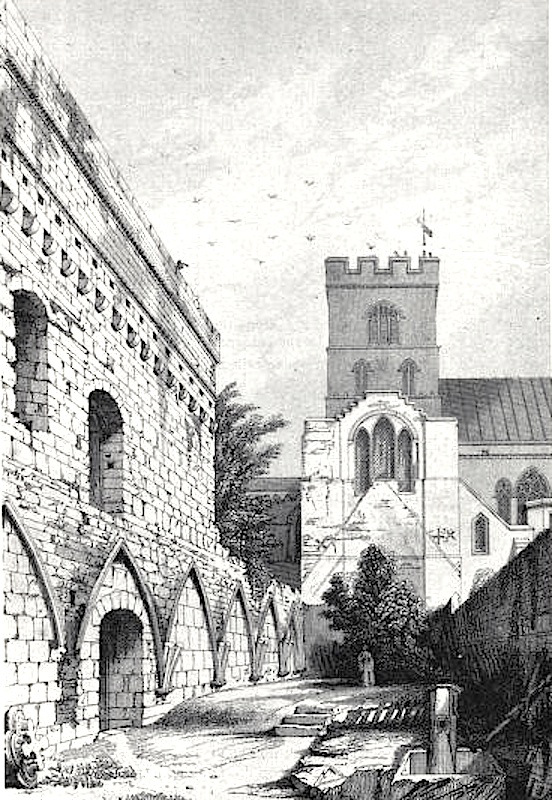

Left: Plan of the cathedral, showing the short nave, which Street opened up. Source: Eley, facing p. 92. Right: East end of the fratry or refectory, restored by Street, and south transept. Source: Eley, facing p. 62.

Another oddity of Carlisle Cathedral is that, along with St Paul's and Llandaff, it never saw the hand of Sir George Gilbert Scott (see Lehmberg 280). But it did get some attention from another giant of Victorian architecture, George Edmund Street. Street's work of 1871 focussed on what was left of the nave, which is only 39' long compared to the choir's 134' (Eley 92); and the fratry, the canons' dining-hall. As for the former, "in 1871, under Mr. Street, the pews were pulled out, and the fragment of the nave thrown open to the rest of the church" (Ferguson 59) — the latter by removing an earlier partition that separated nave from crossing. Later, "Mr Street very carefully restored the fratry in 1880, and it is now used as a chapter-house, library, and choir-school" (Eley 73). Street also designed some new fittings, like the Bishop's oaken throne of 1881 — with, again according to Eley, a canopy nearly 30' high (53). This, however, is the only piece that is still to be seen there (see Hyde and Pevsner 225).

A Continuing Process

Left: Wood carving in the choir, with the pipes of the Willis organ in the background. Right: High altar and reredos, close-up, with the Latin for "For God so loved the world" across the top of the reredos.

Despite some obvious disjunctions in the fabric, like the differently coloured building materials and the asymmetries, much Victorian work is woven seamlessly into what we see today. The choir, for example is greatly admired for its fine choir stalls with their arms carved with foliage and figures, their early fifteenth-century misericords, and the sets of medieval painted panels at their backs. These are priceless treasures. But it also features a fine Willis organ. This too is notable. Only Henry Willis's second cathedral project, this was "the first instrument in an English cathedral to be screened by a simple pipe display without formal casework" ("The Cathedral Organ"), though extra pipes were added in 1875, and, inevitably, more work has been done on it since. The unusual grey stone font was a Victorian offering as well: it was designed by Sir Arthur Blomfield, with canopied bronze figures by F. W. Pomeroy, and was presented to the cathedral in 1891 (see Eley 26).

One of the most important later additions has been the high altar, its importance emphasised by a filigree baldacchino intricate enough to look rich and grand, but light enough not to obscure the east window. This, together with the reredos, was the contribution of a slightly later figure in the world of ecclesiastical design, Sir Charles Nicholson (1867-1949), brother of the stained glass artist A. K. Nicholson, whose own work can be seen in the easternmost window of the south choir aisle (see Hyde and Pevsner 233). The altar, baldacchino and reredos were installed in 1936. The lower choir stalls were also added by Charles Nicholson, and these in turn were extended later in the twentieth century.

As with other cathedrals, conservation and careful updating of amenities, such as seating and lighting, are continuous processes. But it is possible that Carlisle Cathedral would not be here at all today without the concerted efforts of the Victorian architects who worked to save and restore its very fabric. Like others who undertook such tasks at the time, Ewan Christian is sometimes criticised for his heavy-handedness. Yet Tait's and Purday's lectures from that period show a keen interest in the cathedral's history, and there is much to suggest that he strove to preserve whatever he could, as well as to strengthen the structure, make it more accessible, and highlight its most impressive features. The restoration of Carlisle Cathedral is rightly considered one of his most important works.

A portion of the distant tracery glass of the east window, restored by Wailes, in which the wicked are sent down to burn in hell. The figures are tiny from below, but "the red glare of the Place of punishment makes it easy to be distinguished" (Eley 48).

Related Material

- Monument to Bishop Goodwin

- Monument to Bishop Close

- Memorial to George Moore

- Font, by Sir Arthur Blomfield and F. W. Pomeroy

- St Albans Cathedral and Abbey Church, Hertfordshire: A Case History in Victorian Restoration

Sources

Billings, Robert William. Architectural Illustrations, History and Description of Carlisle Cathedral. London: T. and W. Boone, 1840. Internet Archive. Uploaded from the Research Institute, the Getty Library. Web. 23 July 2014.

"Cathedral Church of the Holy and Undivided Trinity, Carlisle." British Listed Buildings. Web. 23 July 2014.

"The Cathedral Organ" (from the Cathedral files). Web. 23 July 2014.

"The Ceiling of the Choir." Carlisle Cathedral (the Cathedral's own website). Web. 23 July 2014.

Chesworth, M. "Life-Size Statues Removed." Cumberland News. 20 July 2007. Web. 23 July 2014.

Eley, C. King. Bell's Cathedrals: The Cathedral Church of Carlisle: A Description of Its Fabric and A Brief History of the Episcopal See. London: George Bell & Son, 1900. Internet Archive. Uploaded from Robarts Library, University of Toronto. Web. 23 July 2014.

Ferguson, Richard Saul. Carlisle Cathedral. London: Ibister, 1898. Internet Archive. Uploaded from the University of California Libraries. Web. 23 July 2014.

Hyde, Matthew, and Nikolaus Pevsner. The Buildings of England: Cumbria: Cumberland, Westmoreland and Furness. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2010.

Jefferson, Samuel. A Guide to Carlisle; or, Historical and Descriptive Accounts of that Ancient City, its Cathedral, Castle, Convents, etc. etc. Samuel Jefferson, 1842. Google Books. Free E-book. Web. 23 July 2014.

Lehmberg, Stanford. English Cathedrals: A History. London: Hambledon, 2005.

Pepin, David. Discovering Cathedrals. Botley, Oxford: Osprey, 2004.

Pevsner, Nikolaus. The Buildings of England: Cumberland and Westmoreland. London: Penguin, 1967.

Pevsner, Nikolaus, and Priscilla Metcalf. The Cathedrals of England: Southern England. London: Viking, 1985.

Tait, A. C., and Charles H. Purdy. Two lectures on Carlisle Cathedral: Historical and Architectural. Carlisle: Charles Thurnham and Sons, 1859. (Note: the second essay, by Purday, starts at p. 1 again.) State Library of Victoria. Web. 23 July 2014.

Last modified 23 July 2014