The following biography of Butterfield comes from the 1901 Dictionary of National Biography, Supplement, Vol. I: Abbott-Childers: 360-63, contributed to the Internet Archive by Robarts Library, University of Toronto. Subtitles, links and images have been added to the text, as have some extra comments in square brackets, and a brief up-to-date select bibliography. On the other hand, cross-references to the DNB itself have been omitted. Such omissions are indicated by ellipses, also in square brackets. [Click on all images to enlarge them and obtain additional information.] — Jacqueline Banerjee.

Parents, education, and early career

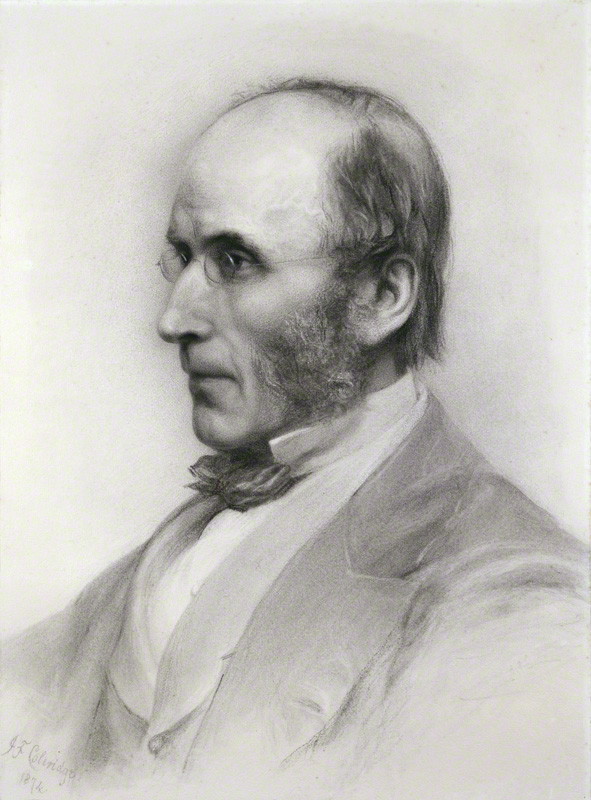

William Butterfield, by Jane (née Fortescue Seymour), Lady Coleridge, in black chalk with touches of black and white ink on handmade paper, laid on to card, 1874; 577 mm x 426 mm, © National Portrait Gallery, London, by kind permission (NPG 6792).

Butterfield, William (1814–1900), architect, the son of William Butterfield, by his wife Ann, daughter of Robert Stevens, was born in the parish of St. Clement Danes, London, on 7 Sept. 1814. His first architectural education was received in an office at Worcester, where a sympathetic head clerk of archæological tastes encouraged him in those studies of English mediæval building which laid the foundation of his career and knowledge (Builder, 1900, lxxviii, 201). He measured and drew the cathedral at Worcester so as to know it in every detail; and at the close of his pupilage he continued this personal examination of buildings in other parts of the country, doubly important from the fact that at that period the gothic structures of England had neither been efficiently recorded nor "restored." Pugin was practically the only gothic architect of the day, and [Thomas] Rickman's "catalogued examination of English churches was a useful pioneer no more" (R. I. B. A. Journal, 1900, vii, 241). [In her new entry in the current ODNB by Rosemary Hill tells us here that "his first significant commission was for his uncle, W. D. Wills, the Bristol tobacco manufacturer, for whom he built the Highbury Congregational chapel" — completed in 1840, in a style showing how much he had learned from Pugin.] Butterfield's inclinations led him naturally into collaboration with the Cambridge Camden Society, among whose founders he had many personal friends, especially the Rev. Benjamin Webb [...] , on whose advice in church matters he placed a high value, and in consultation with whom he prepared a great number of illustrations for the "Instrumenta Ecclesiastica" (London, 1847, 4to), a repertory of church design.

Work for the Cambridge Camden Society, and other earlier work

Left to right: (a) Interior of Balliol College Chapel. (b) Interior of All Saints' Margaret Street. (c) Keble College, seen from Parks Road.

Under the auspices of the Cambridge Camden Society, a scheme was started in 1843 for the improvement of church plate and other articles of church use, and Butterfield, whose offices were then, as throughout his career, at 4 Adam Street, Adelphi, was appointed the "agent." He was, in fact, not merely the receiver of orders but the designer of the goods and the superintendent of their execution (Ecclesiologist, 1843, p. 117).

In 1844 Butterfield designed for Coalpit Heath, near Bristol, a small church to seat four hundred (ib. 1844, p. 113), and in the next year he undertook for Alexander James Beresford-Hope [...] his first important work—the re-erection of St. Augustine's, Canterbury, as a missionary college. This building (ib. vii. 1) shares with the church of St. Matthias, Stoke Newington (1853), and with the collegiate church (now cathedral) of Cumbrae, a certain simplicity and adherence to type which is absent from Butterfield's later and more individual works. The chapel at Balliol College, Oxford (1856–1857), a small but characteristic building, shows the beginning of his unusual methods in colour; but the first church which made his reputation as an architect of undoubted originality was All Saints', Margaret Street, London, which, with its adjoining buildings (1859), forms a significant and admirable group of modern ecclesiastical architecture (ib.xx.; BERESFORD-HOPE, English Cathedrals of the Nineteenth Century), pp. 234, 250). The type of gothic adopted here is, so far as it follows precedent, that of the fourteenth century, but there is great freedom in the handling of forms and mouldings, and an exuberance in the colour decoration. One of the striking features of the church is the, then novel, use of exposed brickwork, both external and internal.

Merton College's venerable medieval chapel, restored by Butterfield in 1864.

All Saints' was followed in 1863 by St. Alban's, near Holborn [...], a building of singular majesty, in which the fine proportions more than counterbalance the idiosyncrasies. A sketch (Builder, xlvi. 1884), made by Mr. A. Beresford Pite, when the houses in Gray's Inn were demolished, shows an aspect of the building generally invisible. The new buildings at Merton College, Oxford (Ecclesiologist, xix. 218), with restoration of the chapel, were entrusted to Butterfield in 1864, and in 1868 he carried out the Hampshire county hospital, which, with St. Michael's Hospital, Cheddar, is among the chief of his non-ecclesiastical works. His next important design was for the chapel and other school buildings at Rugby (1875), and about the same time there came the great opportunity of his life, the commission to build Keble College at Oxford. Of this undertaking the chapel, completed in 1876 at a cost of £60,000, was intended to be the point of central interest. Its proportions and forms are good; but its colour, whether in marble, glass, or other materials, is generally acknowledged to be unfortunate. It is only fair to mention that the chapel has undergone certain alterations by another hand. [However, according to the college's own site, "Apart from the addition of the side-chapel built in 1890 to house The Light of the World, a development opposed by the architect, the Chapel remains largely as he left it.]

Later work and restorations

Butterfield's chief interest lay essentially in his ecclesiastical buildings; but he designed various domestic works, chiefly for his personal friends. Heath's Court, near Ottery St. Mary, erected in 1883 for Lord Coleridge, is one of his best houses, and Milton Ernest in Bedfordshire another. He made the plans for the laying out of Hunstanton, and designed several houses for Mr. Le Strange.

Among his later designs are the chapel and other buildings at Ascot Priory [...], completed in 1885, and the church at Rugby in 1896.

Butterfield's works of restoration were not as happy as his original designs. It is strange that one who based all his knowledge upon original study and who had a genuine love of old buildings should have produced such misinterpretations of antiquity. At Winchester College, where he built certain new buildings, he incurred criticism by destroying the seventeenth-century stalls of the chapel (which may perhaps have been decayed); at St. Cross Hospital he employed, in the name of restoration, a very startling scheme of colouring; at St. Bees he made additions incongruous to the fabric, including a costly iron screen. At Friskney, Lincolnshire, and Brigham, Cumberland, there are further examples of his somewhat unsympathetic attention to old churches.

Butterfield had several commissions for colonial work, designing churches (mostly cathedrals) for Melbourne, Adelaide (Ecclesiologist, v. 141), Bombay, Poonah, Cape Town, Port Elizabeth, and Madagascar. In the case of the first named, Butterfield's advice was withdrawn during the progress of the work, and the finished interior by no means represents his intentions (HOPE, English Cathedrals, pp. 96, 104).

Works not yet mentioned

Left to right: (a) Exterior of St Augustine in Queen's Gate, London. (b) The Sanctuary of St Mary Magdalene, Enfield. (c) Interior of St Augustine's Church, Penarth.

Of his works not yet mentioned the most important are the church of St. Augustine in Queen's Gate, London, another church of the same dedication at Bournemouth, St. Ninian's Cathedral at Perth (completed in 1890; see HOPE, English Cathedrals, p. 78), the chapel at Fulham Palace, the ecclesiastical college in the close at Salisbury, the guards' chapel at Caterham barracks, and the Gordon Boys' Home at Bagshot.

Butterfield's name is also associated with work at St. Michael's Hospital, Axbridge; the grammar school at Exeter; St. Mary's Church in Dover Castle; the church and vicarage of St. Mary Magdalen at Enfield; the chapel of Jesus College, Cambridge; Babbacombe, near Torquay, where Devon marble was employed; West Lavington, with a shingle spire; St. Thomas, a red-brick church, at Leeds; St. John's, Huddersfield; Emery Down, in the New Forest; Baldersby, near Lincoln; Yealmpton, Devonshire; Ardleigh, Essex; St. Mary's Brookfield, Harrow Weald, Middlesex; St. Clement's, City Road; St. John's, Hammersmith; and St. Luke's Church, Sheen, Staffordshire, recast by Butterfield in 1852, his friend Webb being perpetual curate, and Beresford-Hope patron of the parish. Churches at the following places are also all of them original works by Butterfield: Ashford, Aberystwith, Barnet, Brookfield, Barley, Bamford, Beechill, Belmont, Braishfield, Battersea (college chapel), Clayton, Christleton, Clevedon, Cowick, Caer Hill, Dandela, Dalton, Dropmore, Dublin (St. Columba College chapel), Edmonton, Ellerch, Etal, Foxham, Horton, Hensall, Hitchin, Highway, Kingsbury, Landford, Lincoln (Bede chapel), Langley, Lamplugh, Milton Ernest, Netherhampton, Newbury, Portsmouth, Penarth, Poulton, Pollington, Rotherhithe, Rangemore, Ravenswood, Weybridge [St Michael and All Angels, since demolished], Waresley, and Wykeham.

Aspects of Butterfield's working life

Though he contributed valuable articles to the Ecclesiologist, the organ of the Cambridge Camden Society, Butterfield was otherwise an infrequent writer, and almost his only independent publication was a small book on church seats and kneeling boards (2nd edit. 1886; 3rd edit. 1889).

Having a large practice Butterfield naturally employed assistants, and, though he was himself an excellent draughtsman, he was careful, at least in later life, to commit all his working drawings to his subordinates; but he submitted their work to such untiring correction that all he sent out from his office may be looked upon as emphatically his own. [In her contribution to Butterfield Revisited, Hill reinforces this point, showing him "forcing his own vision" on those that assisted him, so that, for example, his stained glass was indeed "'by' him in every significant sense," 10.] His life was one of singular seclusion. It was his care to make it as quiet and retired as was consistent with his public engagements.

Butterfield's work cannot be considered apart from the inner spirit of the church revival; his art was entirely inspired by keen churchmanship, and his churchmanship was based on something deeper than ceremonial. Taking the minutest interest in the details of traditional worship, he held in horror anything like fancy ritual. He instilled into the craftsmen associated with him something of his own scruples against working for the Roman church, and something of his own willingness to labour, if need be without reward, for the church of England. He was associated with various conventual buildings erected for the English church, providing designs both for Miss Sellon's establishment at Plymouth [...] and for the novitiate wing at Wantage, in which town he also carried out St. Mary's School and King Alfred's Grammar School. He interested himself in the problem of providing cheap churches, and once designed a model church to cost £250. It was intended to be without porch or even pulpit, and the bell was to hang on a neighbouring tree. As a matter of fact, Butterfield more than realised his intention, for his church at Charlton, near Wantage, cost under £250, and had porch, bell-turret, and pulpit.

[Looking at Butterfield's last phase, Hill comments in the current ODNB entry, "As well as reflecting the effects of age and an inflexible character, Butterfield's later career also perhaps suffered from that loss of confidence that characterized his generation. The implications of evolutionary theory, to some extent subsumed into a Christian view of creation by the use of minerals and marbles in structural polychrome, were by the end of the century unanswerable. 'The faith & the tradition which made strong men of our fathers are going,' Butterfield wrote to Coleridge (letter, 10 June 1883, priv. coll.). 'There will shortly ... be nothing left for us to believe in but ourselves, and that faith ... is comfortless' (ibid.)."]

Reputation

It is in the matter of colour that Butterfield has been most attacked by his critics, and it is certain that on this subject his views did not coincide with those even of his friends. It may be pointed out, in defence, that in the case of All Saints' Church, and others of that period, his colour theory seems to have been that such combinations were permissible as could be produced by uncoloured natural materials. This theory will account for the juxtaposition of strongly discordant bricks and marbles, and the bright contrasts thus obtained led on, upon Butterfield's own admission, to his strange choice of garish colours in glass; but this plea of "natural" colour cannot be made to cover his views upon the use of similar contrasts in paint. Nor indeed does the consideration that he made a special study of colour in Northern Italy satisfactorily explain the use under the English climate of what may have seemed beautiful beyond the Alps. Still, if in colour and in other matters his work sometimes exhibited originality at the expense both of beauty and of traditional usage, it must at all events be acknowledged as invariably sincere, substantial, and fearlessly true. [Criticism of Butterfield's polychromy could be vicious: his contemporary Benjamin Webb wrote of All Saints' Margaret Street "the colouring throughout seems fragmentary and crude" (qtd. in Brandwood 30). More recent critics have marvelled over it, however, and seen it as essential to the whole scheme of his buildings. With reference to the same church, for example, Colin Kerr writes: "Decoration is used as an essential component, a continuo, tying all together, making meaning" (132). Nor was it deploed indiscriminately: colour was confined to "the floor, the font, and the sanctuary wall and window" in two-thirds of Butterfield's church interiors (Thompson 232).]

Butterfield died, unmarried, on 23 Feb. 1900 at his residence, 42 Bedford Square [seen above right]. He was buried at Tottenham cemetery. He had been a constant attendant at the church of All Hallows, Tottenham, which he had practically rebuilt.

Waterhouse's bibliography

Royal Institute of British Architects Journal (with copy of portrait by Lady Coleridge), vii. 241; Builder, 1900, lxxviii. 201; (Builder, xlvi. 1884) Times, 26 Feb. 1900; Men and Women of the Time; information from the Rev. W. Starey. Ecclesiology 1843, 1844 ib. xx. 184; BERESFORD-HOPE, English Cathedrals of the Nineteenth Century, pp. 234, 250.

Sources of added information

Brandwood, Geoff. "High Anglicanism and High Places: The Rise of William Butterfield." In Howell and Saint. 17-33.

Hill, Rosemary. "Butterfield, William (1814–1900), architect and designer." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Online ed. Web. 8 March 2017.

_____. "A perplexing and challenging character: Butterfield the Man." In Howell and Saint. 7-15.

Howell, Peter, and Andrew Saint, eds. In Butterfield Revisited. Studies in Architecture and Design. The Victorian Society Journal. 6 (2017).

"Keble's Architecture." Keble College. Web. 8 March 2017.

Kerr, Colin. "Restoring All Saints' Margaret Street: Discoveries and Reflections." In Howell and Saint. 123-141.

Thompson, Paul Richard. William Butterfield. London: Routledge, 1971.

Created 8 March 2017